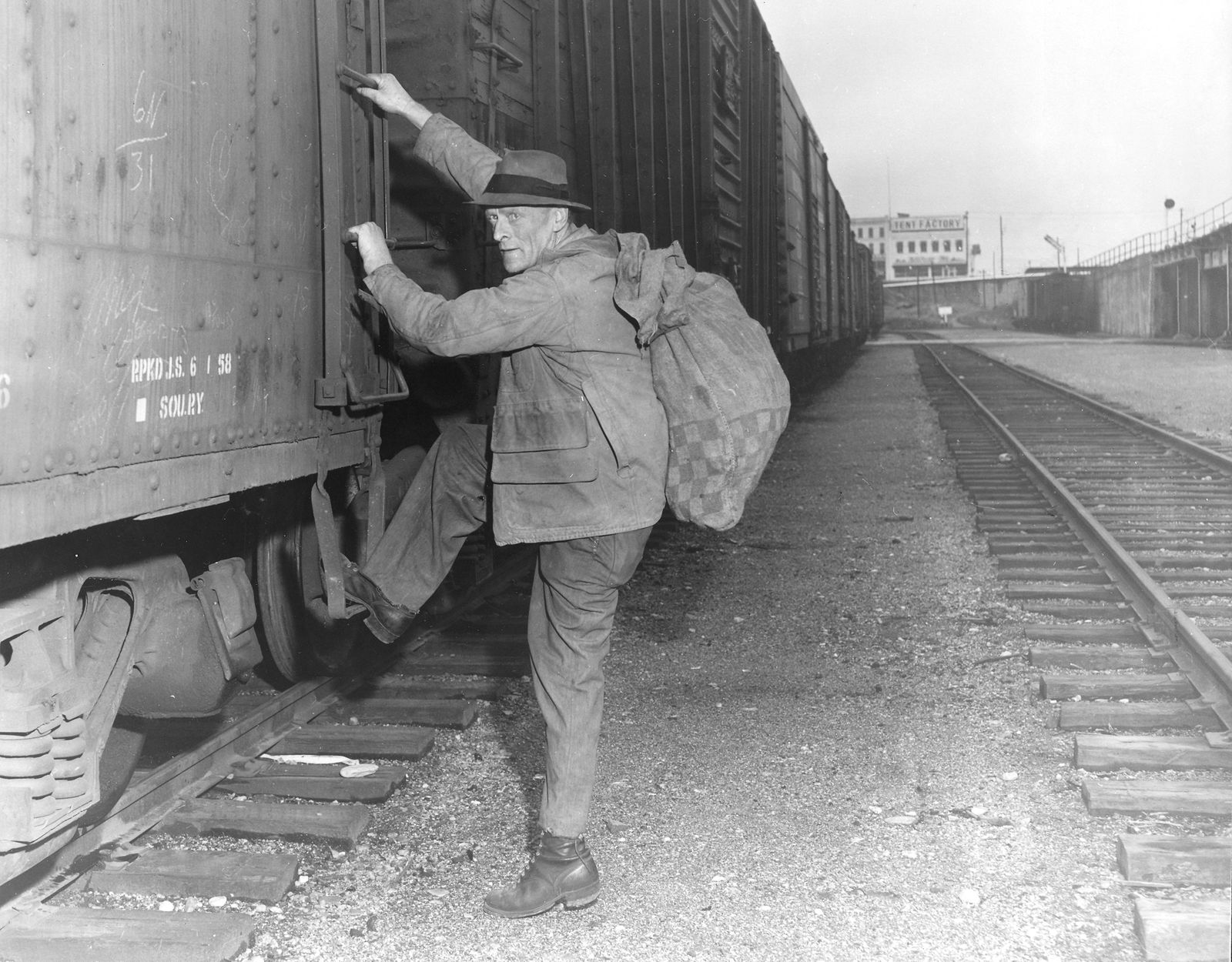

“Some other town, some other day, may be better” was the caption on this photo when it ran with a special report on Spokane’s train hobos, written by Dorothy Rochon Powers and published in November 1958.

Photo archive The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

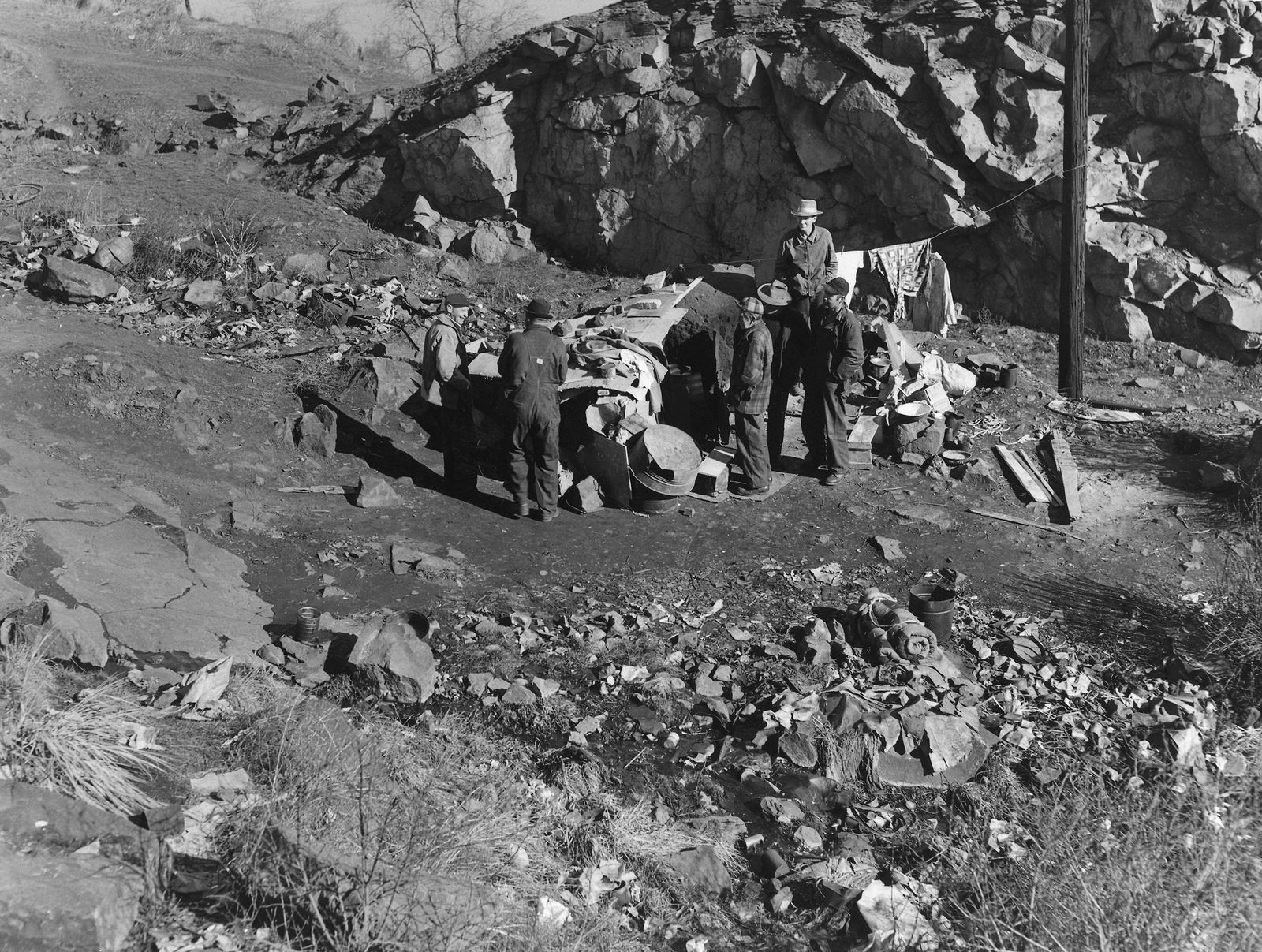

“A man’s his own boss in this hobo camp” featured in a story in The Spokesman-Review in 1953. Bill, far right, drinks coffee from a can.

Photo archive The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

Spokane’s “hobo jungle,” along the banks of the Spokane river, was by a clear spring which furnished drinking water and a place to wash.

Photo archive The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

Woman on the right in this Nov. 19, 1958, photo is Dorothy Powers, Spokesman feature writer.

Photo archive The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

In 1985, train hobos on a cold night share the warmth of the fire inside their galvanized steel pipe.

Photo archive The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

In a Freight Train Riders of America hobo transient camp along the Spokane River, Spokane police Officer Bob Grandinetti photographs each gang member for his files in 1997. Grandinetti became a nationally recognized expert on the gang.

Photo archive The Spokesman-Review

In the 1990s, Grandinetti noticed that the benign hobos of his childhood had disappeared. The new rail riders often formed gangs who robbed and sometimes murdered.

With the backing of his police department, and city officials, he orchestrated a campaign to rid Spokane of train hobos, especially the Freight Train Riders of America who drank fortified Thunderbird wine as part of their hobo code.

A BNSF freight train rolls through the Marshall area south of Spokane on Aug. 11.

Christopher Anderson The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

Christopher Anderson The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

A BNSF freight train rolls through the Marshall area just south of Spokane on August 11, 2011.

Christopher Anderson The Spokesman-Review Buy this photo

He didn’t.

Share on Social Media