Lolo wolves killed to give famous elk herd a break

Updated March 11, 2015:

PREDATORS -- Nineteen wolves were killed in Idaho’s Lolo region last month in an ongoing effort to improve elk survival in the rugged area on the Idaho-Montana border.

Federal Wildlife Service agents shot the wolves from an aircraft at the request of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. State officials say that both habitat changes and predation are responsible for the Lolo’s declining elk herds.

The Lolo elk population has dropped from 16,000 elk in 1989 to roughly 2,100 elk in 2010, and possibly fewer than 1,000 this year. State studies indicate that wolves have become the primary predator affecting calf and cow elk survival in the Lolo.

Read more here.

- Update March 11: Idaho lawmakers vote to renew wolf-kill program funds

- See the Lolo predation management plan.

- See the 2014 Idaho Elk Management Plan.

Here's more detail from Eric Barker, outdoor writer for the Lewiston Tribune:

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game killed 19 wolves in the state’s remote Lolo Hunting Zone last month, part of a years-long campaign to help the ailing elk herd there by reducing predator numbers.

The controversial action, carried out by the U.S. Wildlife Services agency at the department’s request, was announced Monday and brings the total number of wolves killed by state and federal agents in the Lolo Zone to 48 over the past five years, including 23 in 2014. Most of the wolves were located with and shot from helicopters.

Jerome Hansen, supervisor of the department’s Clearwater Region, said the wolves were killed as part of a larger effort to improve elk survival. Elk numbers in the Lolo Zone have dropped dramatically over the past 26 years. In 1989, the department estimated the area had about 16,000 elk. A 2010 survey estimated the herd had dropped to 2,100 animals, and the department now believes it may be as low as 1,000.

Wildlife biologists have said changing habitat - mainly the loss of productive brush fields that contain ample food for elk and the succession from young open forests to denser stands of timber - as the primary problem that prompted elk numbers to crash. But they also said predation by wolves is keeping elk from rebounding.

"We have to manage wolves aggressively in order to get elk turned around," Hansen said. "It’s going to take work on implementing the (predator management plan) year after year and it’s going to take doing whatever we can do with habitat. We don’t control the habitat side but we are going to keep working with the Forest Service and the (Clearwater Basin Collaborative) to improve the habitat."

The Lolo Zone is remote with few roads. That limits the ability of hunters and trappers to access the area.

"In a perfect world our sportsmen would be able to manage wolves to the extent we really need to but it’s so tough to get in there it’s about the only tool we have," he said.

Suzanne Stone of the Defenders of Wildlife at Boise took issue with that rational.

"If it’s so remote that hunters can’t get in there why would hunters care that wolves are killing elk in there?" she said. "In order for wolves to be impacting hunters you have to have hunters in the area and what they have been telling us all along is there’s not a lot of people hunting this area and actually few that get far back in there."

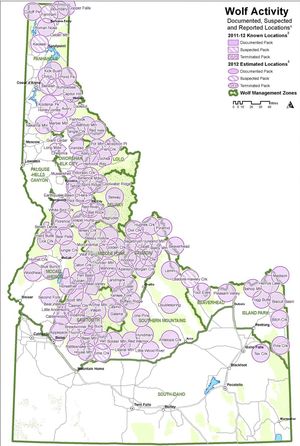

So far this year, hunters and trappers have taken 11 wolves in the zone. According to the department’s latest wolf survey, completed a year ago, the Lolo Zone had an estimated wolf population of 75 to 100. A new survey is expected to be released later this month.

The department’s Lolo Predator Management Plan calls for reducing wolf numbers by 70 to 80 percent. Many wildlife biologists say wolves can sustain an annual harvest rate of up to 40 percent without reducing overall numbers.

Following its policy, the department kept the control action under wraps until it was complete. Fish and game spokesman Mike Keckler cited safety concerns as the reason but declined to elaborate.

"I’m not going to get into that. It’s just our safety issues," he said. "In that country in particular, these can be dangerous operations. We prefer to get it done and then let folks know about it after the fact."

The Nez Perce Tribe, which has some wolf management authority and played a central role in wolf reintroduction efforts, has taken issue with the state’s previous efforts to cull wolves in the Lolo Zone. Representatives from the tribe could not be reached Monday for comment.