Ask the Builder: Misconceptions about house ‘settlement’

Roy subscribes to my free newsletter. He reached out to me about a month ago for one of my phone consultations. He needed help engineering a drainage system around his house to stop water from infiltrating his basement. My college degree is in geology with a focus on hydrogeology and geomorphology. Hydrogeology is the study of groundwater movement. Geomorphology is the study of the earth’s surface where we walk and build things.

I shared how to stop the water infiltration. Roy emailed me a few weeks later to report my advice yielded a dry basement. He was happy. He asked for additional advice based on some information given to him by a neighbor. All of a sudden we were on the topic of house settlement. His neighbor wandered into the murky depths of a problem that’s misunderstood and misdiagnosed perhaps tens of thousands of times a day across the USA and the world.

I could write a book about the topic of house settlement. It’s impossible to give it the thoroughness it deserves in this tiny column. I’ll attempt now to cover some of the most important aspects of the topic.

I pulled out my trusty dictionary made with paper and found that one of the many definitions of the word settle is “to cause to pack down.” This explains why many feel their house settles or sinks into the ground after its built.

For the most part, houses and buildings rarely sink or settle. Most soils are strong. When a house, or part of one, sinks, it can be caused by landslides, earthquakes, uncompacted soil, buried vegetation that rots, expansive clay soil movement or glacial clays that ooze like toothpaste, among other factors.

Roy’s neighbor said settlement causes cracks in foundations that permit water infiltration. This is a true statement, but most foundation cracks in poured concrete foundations are caused by shrinkage, not settlement. Concrete shrinks 1/16 inch for every 10 feet of length as it cures over time. You’ll often see the cracks radiating at an angle from the corners of basement windows or any other hard 90-degree angle in an opening in the wall.

Concrete block foundations often develop horizontal cracks between layers of block. These cracks are often about 4 feet up from the basement floor. These are rarely caused by settlement. The cause can be traced to the inability of the thin mortar to withstand the tension forces applied to the wall. Remember, basement foundation walls are simply retaining walls holding back the earth outside.

The earth presses sideways against the walls and causes them to want to bend inwards. This bending force creates tension or stretching. If the block mason had filled the hollow cores of the concrete block with pea-gravel concrete and put a steel rod from the top of the wall to the footing in every other vertical core void, there’s a good chance there would not be a horizontal crack.

Keep in mind that Mother Nature is good at compacting soil. She uses both rain and gravity. Most soils are strong, as is evidenced by the countless houses and buildings that are hundreds of years old that have no structural defects relating to soil movement.

I recall a job in Cincinnati. Forty years ago, I had to build a room addition on a home. The house was so old it had a stone foundation. My room addition floor had to be lower than the existing basement. I carefully dug along the old stone foundation trying to locate the footing. There was none. The builder just laid the first row of stone on the dense clay soil. The house was over 100 years old and had experienced no settlement of the foundation even with the concentrated load of the house on the soil.

Many cracks that appear in the floors, ceilings, tile, drywall and woodwork of new homes are often blamed on settlement. In almost all cases the cracks can be blamed on hybridized lumber. Trees are a crop not much different from soybeans and strawberries. The only difference is harvest time. Lumber companies, I believe, have engineered trees to grow faster so stands of timber can be harvested faster.

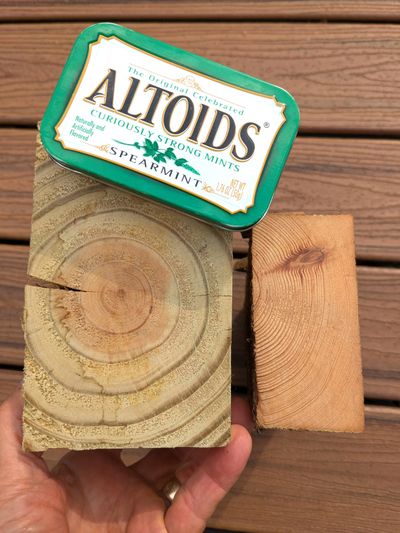

Trees grow the most in spring. The wood produced at this time is lighter in color. The dark bands of growth you see at the end of a stick of lumber are summer wood. Summer wood is denser as the tree slows down its growth most often from a lack of rainfall in the summer. Old-growth timber is markedly different. The spring and summer-wood growth bands are almost always the same size.

The more spring wood in a piece of timber, the more it wants to expand and contract as it experiences changes in moisture content. As the timber in a new home loses moisture, it shrinks, causing the same tension cracks as happens in concrete. Things attached to the timber in your home then start to move creating cracks. These are shrinkage cracks, not settlement cracks.

Subscribe to Tim Carter’s free newsletter at AsktheBuilder.com. Tim offers phone coaching calls if you get stuck during a DIY job. Go here: go.askthebuilder.com/coaching