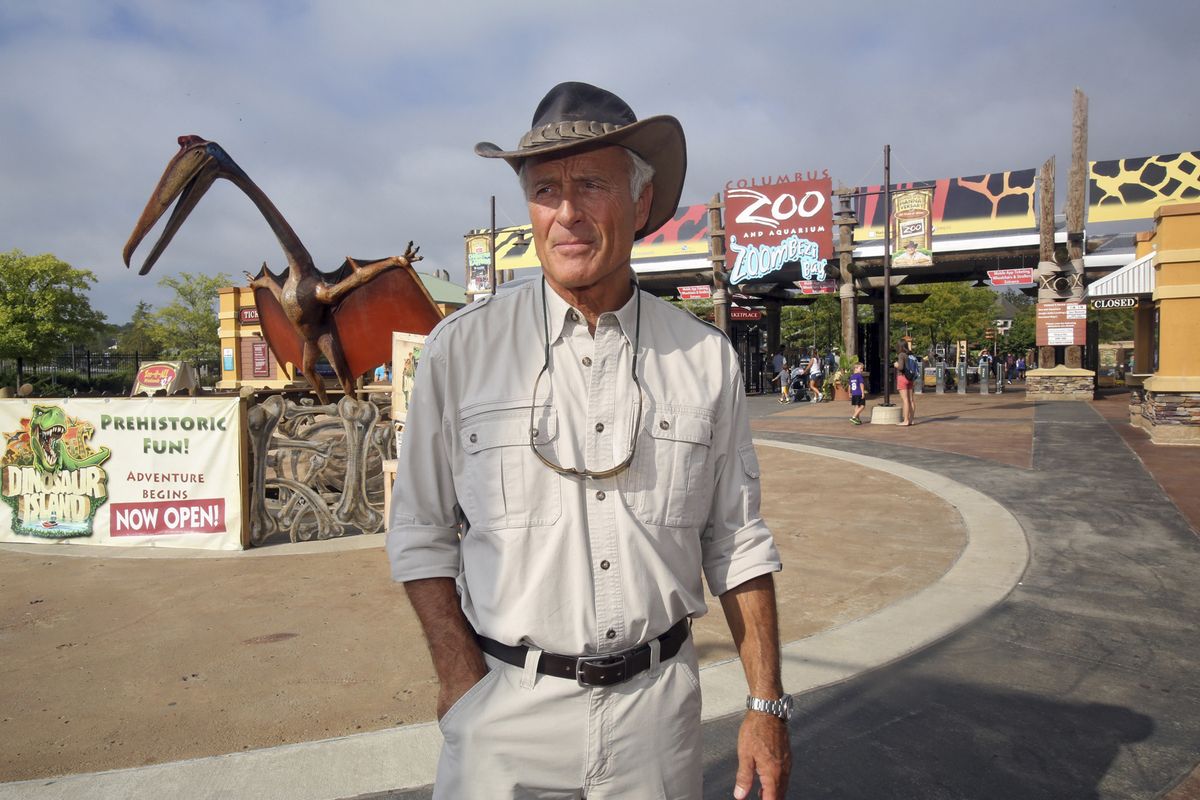

Lions, tigers and an unbearable year at Jack Hanna’s zoo

COLUMBUS, Ohio — The Columbus Zoo and Aquarium had a bear of a year.

It began Jan. 1, the first day of famous zookeeper Jack Hanna’s retirement after 42 years as the beloved celebrity director-turned-ambassador of the nation’s second-largest zoo.

As if the khaki-wearing “Jungle Jack” were the life’s breath of the institution that his upbeat animal-loving persona and masses of TV appearances made famous, the zoo seemed to deflate from there.

In March, news of a financial scandal broke. Top executives resigned. Investigations were launched. Mea culpas were issued.

The next week, the zoo’s beloved 29-year-old bonobo Unga died, and a 4-year-old cheetah injured a zookeeper.

Then in April, just as a streaming international TV channel named for him was launching, a damning animal rights documentary alleging Hanna had ties to the big cat trade premiered in California. A day later, in timing they said was unrelated, Hanna’s family announced he had dementia and would retire from public life.

In October, citing the financial and animal rights revelations, a commission of the respected Association of Zoos and Aquariums stripped the Columbus Zoo of its main accreditation. Zoo officials filed an intent to appeal last week.

“It’s been a tough year for the Columbus Zoo, yes,” said association president Dan Ashe, while adding that the zoo’s roughly 2 million visitors a year can still be assured the facility’s 10,000 animals are well cared for.

Ashe said bringing in Tom Schmid, who currently heads the Texas State Aquarium, as the zoo’s new leader bodes well: “He’s going to bring the Columbus Zoo roaring back.”

Schmid, 56, begins his new job Dec. 6 as president and CEO of the zoo and its related businesses, including The Wilds safari park and conservation center and Zoombezi Bay water park.

Keith Shumate, chair of the zoo’s board, called Schmid “extremely smart, ethical and passionate about zoos and wildlife conservation.”

“We can’t change what happened in the past, but we’ve done a lot to admit those wrongs, to apologize and to address our shortcomings,” said zoo spokesperson Nicolle Gomez Racey. “The people who took liberties in their power are gone, and the people who are cleaning up the mess in the room, under new leadership, we’re moving forward. That’s the only thing you can do.”

Interim CEO Jerry Borin has overseen zoo business since then-CEO Tom Stalf and his chief financial officer, Greg Bell, resigned in March after a Columbus Dispatch investigation found they allowed relatives to live in houses owned or controlled by the zoo and sought tickets for family members to attend entertainment events.

The findings were confirmed in subsequent reviews, including a forensic analysis that found financial abuses by Stalf, Bell and two other former executives cost the zoo more than $630,000. Investigations by Ohio’s state auditor and attorney general are still underway, their spokespeople said.

The spending abuse was a particularly painful blow after the pandemic-related financial hardship of 2020.

Typically, Columbus Zoo is open 363 days a year. More than half its earned revenue comes from admissions and other sales, such as food and gift items. Yet, that year, it was closed for weeks, ultimately sustaining $20 million in operational losses. Twenty-nine full- and part-time employees were furloughed, and 33 non-animal care positions across the zoo and The Wilds were eliminated.

Yet even more wrenching were the accusations leveled in the documentary “The Conservation Game,” which premiered at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival on April 6.

The film tied the zoo and Hanna to the big cat trade, showing that some tiger, lion and snow leopard cubs that had been Hanna’s fuzzy and adorable companions on TV neither came from nor returned to the zoo. In many cases, they were provided by backyard breeders and unaccredited roadside zoos and disappeared into private hands after those appearances.

As publicity around the film grew, Hanna’s relatives said they hadn’t seen it and could not comment on the claims. “What we can say emphatically is that he worked his entire career to better the animal world,” the family said in a statement.

Ashe said the film’s revelations, coupled with his association’s own growing file on the zoo’s Animal Programs department, weighed heavily in the decision to pull Columbus’ accreditation.

“They were, and have been for some time, dealing with non-AZA members, and pretty clearly not disclosing those transfers,” Ashe said. “Those are very serious issues within our accreditation process.”

Filmmaker Michael Webber said the zoo and its accreditors took his documentary’s allegations seriously.

Over the summer, the zoo acknowledged the bulk of the film’s revelations and apologized. It revised policies and reporting structures for acquisition and disposition of ambassador animals in the Animal Programs department. A longtime vice president of animal programs retired.

“We made some mistakes. There’s no doubt about it,” Shumate told the Dispatch.

Borin also reversed the zoo’s previous opposition — which the film alleged had been spearheaded by Hanna — to The Big Cat Public Safety Act. He announced zoo support in April for the federal legislation prohibiting private ownership of big cats as pets and banning cub-petting venues. Racey said the reversal followed important revisions to the bill, which remains pending in Washington.

Webber said he’s giving the zoo a second chance because of its robust response to the film, and he hopes the public will, too.

“I feel very good about the outlook both for the Columbus Zoo and for the animals that we’ve seen exploited for decades,” he said. “Albeit after a very painful year, things are going to be better.”

Ashe said the year’s disclosures also have caused soul-searching within the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, where the Columbus Zoo has long been a flagship institution and Hanna a superstar.

“Our members live on their reputation for excellent care of animals, so whenever we see something like Columbus, which, quite frankly, we should have caught that earlier, it’s an opportunity for reflection and improvement,” he said. “That’s the silver lining in all of this. I think Columbus will be better as a zoological facility, and we’ll be better as an accrediting body, as well.”