WSU, EWU, SCC students face growing dilemma: Pay for food or tuition?

Kianna Baker wasn’t just losing weight, she was losing her hair.

The summer going into her sophomore year at Eastern Washington University, Baker – who had been a member of the women’s basketball team before a medical retirement – was having difficulty buying groceries because of dwindling scholarship money. She remembers occasionally visiting a food pantry in the Women’s and Gender Education Center.

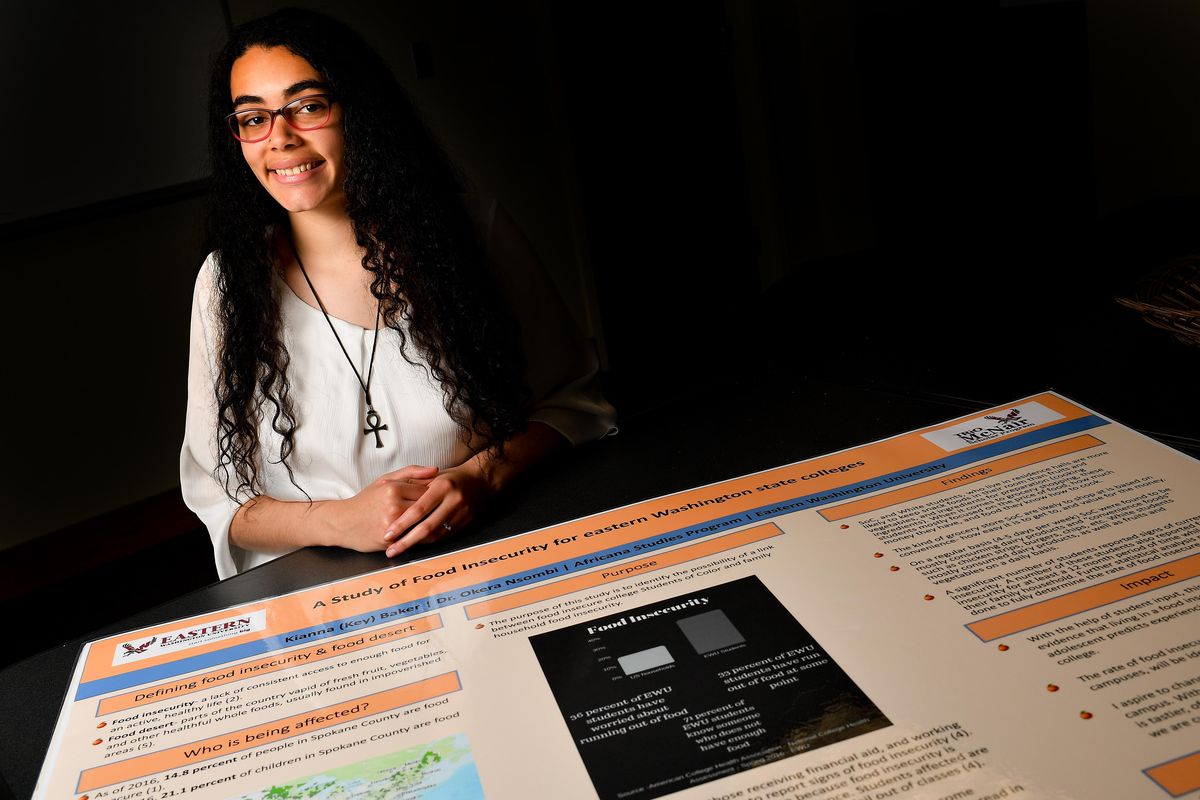

Baker recently was elected Associated Students of EWU president, and a major part of her platform was addressing food insecurity among students.

Thousands of Washington college students are hungry. Washington State University, Eastern Washington University and the Community Colleges of Spokane are struggling with the problem, despite varied approaches.

The local colleges are part of a national trend reported by Temple University’s Hope Center for College, Community and Justice. In the national survey, 48% of students at two-year institutions reported food insecurity within the past 30 days. For four-year institutions, 41% of those surveyed had experienced food insecurity, which is defined as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe food, or the ability to acquire such food in a socially acceptable manner.”

“I’ve experienced it before, and I am very empathetic and compassionate for students,” Baker said. “I’m a big helper, that’s my personality, and something like food … It’s a matter between life and death.”

Baker conducted her own survey, and of the 309 participants, 43% identified as dealing with food insecurity. Baker’s research also looked into those who dealt with the problem prior to college, and found that all who identified as being from food-insecure households also experienced the problem in college. But for Baker, the problem is more than just numbers; it is real, and it is scary.

“There’s actually a student who passed out in our cafeteria just a few weeks ago because all they had been eating is top ramen for, like, weeks on end and their body couldn’t handle it anymore,” Baker said.

Current EWU student president Dante Tyler said Baker’s campaign message appealed to students who recognized food insecurity for the problem that it is. Tyler said he grew up in such a home.

“I think that’s something that a lot of students at Eastern are facing,” Tyler said. “We come from low-income families, we come from families that didn’t really have the money or the wherewithal to get a sufficient amount of food at all times, and even when they did, they didn’t really know the best foods to be buying.”

EWU has several food pantries on campus, but Baker said she is going to work on other approaches, too, including strengthening the community garden, lowering prices of on-campus food and increasing awareness.

Washington State University is addressing student hunger with a program called “Cougs feeding Cougs.”

“We certainly don’t have the funding to solve the food insecurity problem on the WSU Pullman campus,” said Craig Howard, WSU director of administrative services, information systems and the Cougar Card center. “We know that there’s unmet demand.”

Howard is in charge of the “Cougs feeding Cougs” program, which allows students to apply online for $10 increments to be applied to their dining card balances. The program – funded entirely by donations, often from students, parents or alumni – was implemented in February 2017 and has since helped 1,251 students. Of those students, 86 have used the program more than 100 times.

“We see that we have students at WSU who are always stressed by their financial situation and are struggling to find where that next meal is coming from, so that’s the core concern that we have, and the core need that we’re trying to fill,” Howard said.

Aside from “Cougs feeding Cougs,” WSU’s campus also has two official food banks. Rosario’s Place, a food bank within WSU’s Women’s Center, started as a shared clothing closet for children’s clothing and supplies to help student parents.

“It began in memory of a child named Rosario who died,” said Jennifer Murray, WSU Women’s Center program coordinator. “A few years ago, the food bank part of it started when a staff member, not even here but elsewhere on campus, kept overhearing students talking about food insecurity and started bringing in cans of soup to give them.”

Murray said Rosario’s Place runs out of food multiple times a year, and that she thinks the demand is mostly based on how many people know about it.

“For the people who are in a difficult moment, it feels amazing to be able to feed them,” Murray said. “We do everything we can to maintain their dignity and let them know that we’ve all been there, this is a hard chunk, don’t worry, and we’re just glad that we can help.”

Murray said WSU teachers overhearing student conversations has led to a lot of unofficial food banks, as well. Amy Nusbaum, a WSU psychology doctoral candidate, began leaving small things, like granola bars, in her mailbox outside her office.

“That stuff started getting taken more and more frequently to the point where I was like, okay, this is clearly a problem,” Nusbaum said.

She posted about the issue on social media and put together an Amazon wish list.

“It’s now a four-shelf system, and there’s a lot more options and people are pretty routinely sending stuff off that wish list,” Nusbaum said.

Spokane Community College and Spokane Falls Community College struggle with food insecurity, as well, and both have food pantries to assist students.

SCC’s pantry can be accessed by students three times a quarter.

“We’re designed to help students in an emergent need to get a three day food supply, breakfast, lunch and dinner,” said Rachel Moore, SCC food pantry manager. “They just have to have their student ID and a schedule. We don’t ask any other questions.”

Most of the pantry’s supplies come from Second Harvest, which also services the SFCC food pantry. Moore said the SCC pantry sees between 20 and 25 students a week.

SFCC receives between 15 to 25 visits a week, according to Heather McKenzie WaitE, student programs director. For this food bank, a student can visit three times a quarter and receive 15 pounds of food. They also have farmers market produce available once a month, also provided by Second Harvest.

Last year, the CCS Foundation provided emergency support to 1,453 students, said Heather Beebe-Stevens, the foundation’s executive director.

The support included replacement eye glasses, gas vouchers, grocery store gift cards and even rent.

Gonzaga University does not report a significant problem with food insecurity on its campus. Nicola Mannetter, director of the Center for Cura Personalis, said between five and 10 students seek help per semester. In those cases, Mannetter provides the student with resources and in many cases, can provide the student with a free or reduced-price dining card.

According to Feeding America, 14.1% of Spokane County’s total population was food insecure in 2017, but 20% of the children in Spokane County were reported as food insecure.