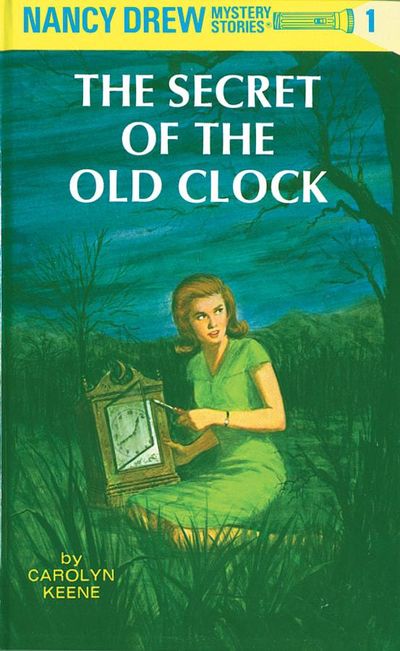

Book World: Why Nancy Drew is an ideal role model for today’s girls (and boys)

Whenever asked what prompted my interest in either of my careers – fighting crime or writing crime – I have always credited my passion for both to my preadolescent devotion to the teenage sleuth who inspired me twice over: Nancy Drew.

I had been a voracious reader as a child, but my memories of discovering a charismatic teenager and her posse of friends who returned in book after book to take on the evil forces in River Heights marked my initial awareness of continuing characters in a series of novels. I admired everything about Nancy – how intrepid she was in her efforts to set things right, her loyalty to her father and her pals, and her bold manner of taking on mysterious situations to right wrongs, even when adults scoffed at her plans.

I loved the storytelling, too. As I grew older, I dreamed of writing tales about a protagonist – a strong woman in a nontraditional role – who might capture a reader’s imagination the way Nancy had captured mine. I wanted, also, to do justice.

I was a member of the last all-women’s class at Vassar College, where I had gone to study literature, clinging to that idea of becoming a writer. Upon my graduation in 1969, I started law school at the University of Virginia – one of about 15 women in a class of 340 students. There were few women role models at the bar and on the bench anywhere in the country when I started practicing law in 1972, the seventh woman on the legal staff of Manhattan District Attorney Frank Hogan. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had recently been created, but that didn’t stop the legendary D.A. from telling me that the prosecutorial job he reluctantly hired me to do was “too tawdry” for a woman of my educational background. He said that I could expect to spend a good deal of my time in the law library rather than the courtroom. Fortunately, that didn’t prove to be the case.

Nancy Drew was my fictional role model throughout most of my youth. I was more fortunate than she in some ways. Nancy had lost her mother when she was 3 years old. She was devoted to her single dad, but they were living in a town rife with crime. I had both loving parents – it was my mother who read to me every night before I went to sleep – and Mount Vernon, N.Y., seemed a much safer place than River Heights. But I did envy Nancy the blue roadster and the steady partnership of Ned Nickerson. That was true until I found my real-life colleagues – mostly guys in the early days – in the D.A.’s office, and we started to solve cases with the great men and women of the NYPD, riding in unmarked black cars on our way to crime scenes. I didn’t leave home with Nancy’s trusty flashlight, but there was plenty of her moxie driving my desire to do the right thing.

I smile whenever I hear an accomplished woman mention Nancy Drew – who made her first appearance in 1930 – as an inspirational figure. Former justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote about being pulled away from Nancy’s exploits to do more serious work on the family ranch; Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg responded to the young woman’s adventurous nature and her daring; and Justice Sonia Sotomayor – who has described reading as her “rocket ship out of the second floor apartment” in a South Bronx housing project – admired Nancy’s character and her courage. Hillary Clinton, too, is a fan, respecting how smart and brave Nancy was, also her ability to multitask: taking care of her dad’s house, keeping up with her schoolwork and solving capers on top of it all. Laura Bush also loved reading Nancy Drew mysteries.

Though the Nancy Drew books have been updated to eliminate racist stereotypes, they suffer from a striking lack of diversity. The folks in River Heights were all white, and the bad guys were always foreign and usually dark-skinned or swarthy. And yet the appeal of the girl detective – she was originally penned as an 18-year-old and later adjusted to 16 – remained widespread. My friend Faye Wattleton spent her preadolescent years in Nebraska, an African-American child whose mother pastored an all-white church. Wattleton told me that Nancy’s “indomitable independence, fearless inquisitiveness and determination to get the job done – never forgetting to ‘freshen up’ her appearance – was a bridge, from multiple layers of isolation to imagining the power of challenging the conventional in order for good to triumph over evil.”

For me, both dreams that emerged from the pages of Nancy’s adventure have come true. I have spent 45 years as a lawyer, fighting for justice for women and children who have been victims of violence. And I have written 21 mysteries – two of them for young readers – in which my protagonists, one a prosecutor and the other a 12-year-old sleuth, channel the character and courage of a fictional heroine. I never wanted to imitate Nancy Drew in either career. But I ached to run along beside her, and that has been a run well worth taking.

Fairstein is a former sex-crimes prosecutor and author of the Alexandra Cooper crime novels and the Devlin Quick middle-grade mystery series. Her new book is “The Devlin Quick Mysteries: Digging for Trouble.”