Two possible paths for Brazil’s most beloved ex-leader: Prison or the presidency

SAO PAULO, Brazil – A little over a year from now, Brazil’s most popular politician might be sleeping in one of two places: in comfort behind the gates of the presidential palace or in a cot behind bars.

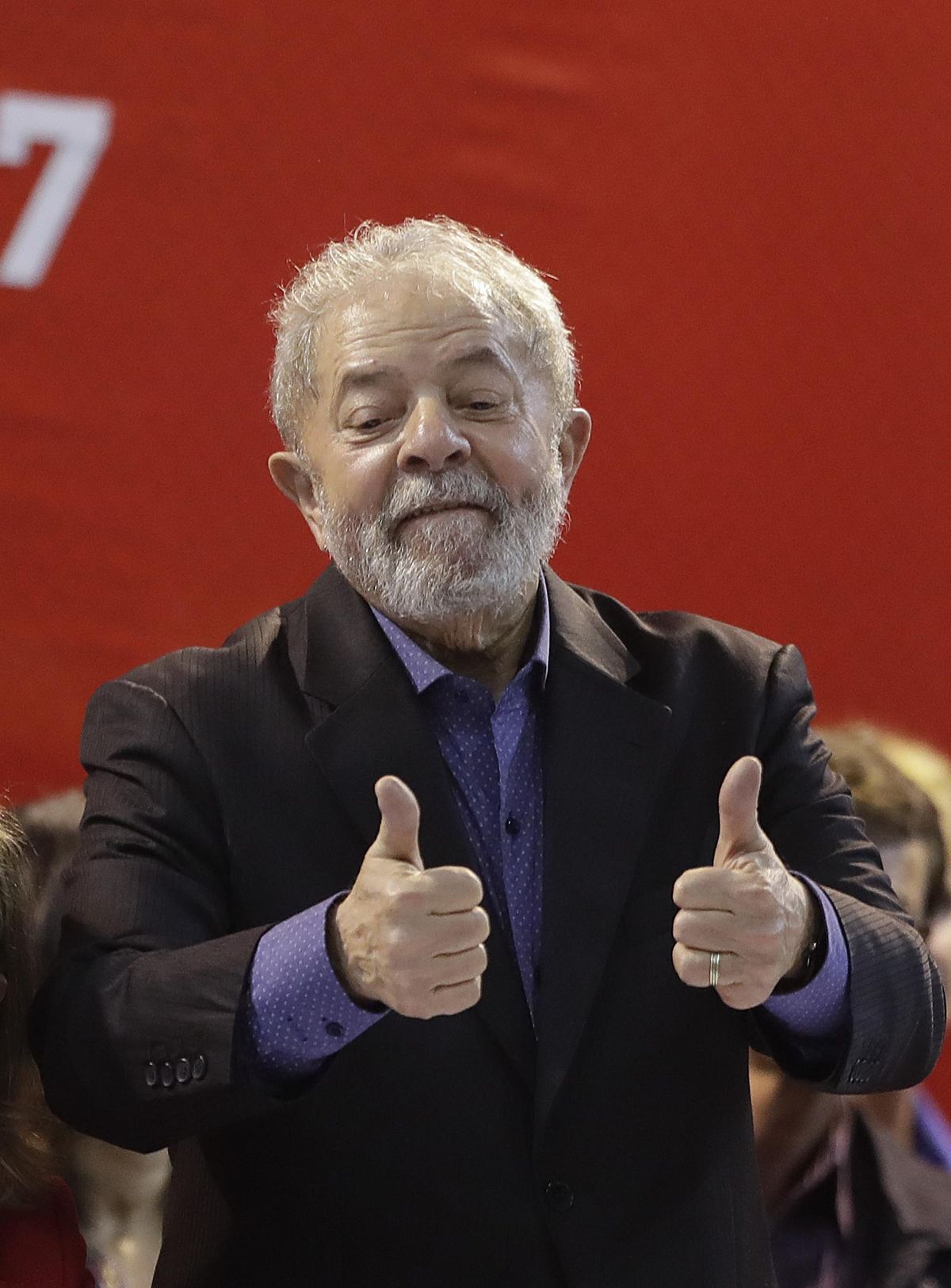

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, popularly known as Lula, guided the country through a honeymoon period of growth as president from 2003 through 2010. Today, he faces five trials for his alleged involvement in a $2 billion kickback scheme that has decimated Brazil’s political elite. If convicted, the 71-year-old could be imprisoned for the rest of his life. But Lula has a shot at an appealing alternative: the presidency. According to the latest polls, the former leader is a clear front-runner in primaries ahead of next year’s election.

The stakes could not be higher. In addition to sending him to prison, a conviction would prevent Lula from running for public office, extinguishing his political career. But if he can stall the judicial process long enough to win the October 2018 vote, including exhausting all of his appeals, he’ll gain presidential immunity, shielding him from prosecution for four years. So Lula’s defense team is taking its time. They have called 87 witnesses to take the stand for one of his trials, a process that could easily run through the election.

A former union organizer with a fourth-grade education, Lula rose to power as a voice for Brazil’s disenfranchised poor. He proved to be an astute and charismatic politician and left the presidency with a dizzyingly high approval rate of 87 percent. During his tenure, millions were lifted from poverty into the middle class and Brazil experienced rapid growth.

The good times, however, would not last. The country was gripped by its worst economic crisis on record, with unemployment rates soaring to a record 13 percent. Still, Lula’s reputation as a champion of the middle class remained largely intact. By the time his political ally Dilma Rousseff was impeached in 2016 with a 10 percent approval rating, Lula was already said to be planning a comeback.

But he soon became the highest-profile figure to be ensnared in Brazil’s “Car Wash” scandal, a scheme in which politicians allegedly accepted bribes and donations in return for lucrative government contracts. Through a series of plea-bargain deals with defendants, prosecutors were able to trace the trail of corruption from a Brasilia car wash to the country’s Congress. Today, a third of the president’s cabinet and a third of the Senate are under investigation.

Led by the Brazilian activist judge Sirgio Moro, a hero to the country’s anti-corruption movement, the Car Wash probe has been a leveling moment in Brazilian politics, signaling that no one, no matter how rich or powerful, is above the law. But whether it can bring down the most beloved politician in the country’s history remains to be seen.

On Wednesday, in a showdown of giants, Lula testified before Moro for five hours, denying accusations that he accepted the refurbishing of a beachfront apartment by one of the country’s major construction firms in exchange for influence. Lula has called the Car Wash probe a witch hunt and claims that the mainstream media and the conservative right are trying to sabotage his bid for another term as president.

Throngs of Lula and Moro supporters descended on the southern city of Curitiba on Wednesday to await the outcome of the historic testimony. In a fiery speech to his red-clad loyalists, a teary-eyed Lula promised to see the process to the end. “I’ll do as many depositions as necessary, because if there is a Brazilian, if there is a human being, searching for the truth, it is me,” he said.

Moro will now hear the final arguments of the defense and the prosecution before ruling. Even if Lula is not convicted, analysts say, the investigations have tarnished his reputation and left his party in shambles. It is unclear whether he can rally his remaining support to get him beyond the primaries and into the presidency.

“His credibility with the middle class has been severely affected over the years because of the corruption scandals,” said Hernan Gomez, an expert on Latin American politics and author of a book on Lula. “He can easily win the first round, but the second won’t be so easy.”