Bride-to-be called 911 for help and was fatally shot by a Minneapolis police officer

MINNEAPOLIS – Justine Damond called police after hearing a sound in an alley near the home she shared with her fianci late Saturday night. But shortly after two officers arrived in her upscale Minneapolis neighborhood to investigate, the call turned deadly when one of the officers shot Damond.

It is unclear why the officer opened fire on Damond, a 40-year-old yoga and meditation teacher from Australia who was supposed to wed next month, and her death immediately drew renewed scrutiny of police officers in the Twin Cities area for their use of deadly force.

Minneapolis is still reeling from two controversial police-involved shootings that set off waves of heated protests and prompted nationwide calls for officers to wear body cameras. One of the cases in recent weeks again led to rallies and condemnation when an officer who shot a black man during a traffic stop was acquitted.

Damond’s death, one of more than 500 fatal shootings by police in the United States this year, also has raised serious concerns in her home country. News of Damond’s death was splashed across the websites of major news outlets in Australia, where friends, according to media reports, are demanding a federal investigation.

Investigators remained tight-lipped Monday about what happened at 11:30 p.m. Saturday, when police received a 911 call about a possible assault in the alley behind Damond’s home. Neither of the responding officers had turned on their body cameras, and police have not yet said why one of the officers shot her. The squad car camera did not capture the incident, either.

The Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA), the state agency investigating the shooting, has said only that “at one point,” one of the officers fired a weapon and struck Damond. No weapons were found at the scene.

Investigators are looking into whether other video of the shooting exists, the BCA statement said. When the state investigation is completed, the results will be given to the office of Hennepin County Attorney Michael O. Freeman for review. A spokesman for Freeman declined to comment about the shooting Monday.

All Minneapolis police officers have worn body cameras since the end of 2016, according to the city, a policy decision that was announced last July, after a black motorist named Philando Castile, a local school worker who was fatally shot by a police officer during a traffic stop in the Twin Cities area. A dash-cam video showed an officer shooting numerous times into Castile’s car but did not show what was happening inside the vehicle; the officer in that case said he believed Castile had been going for a weapon, an account Castile’s girlfriend, who was in the passenger seat, has long disputed.

Authorities said the officers involved in Damond’s shooting have been placed on paid administrative leave, which is standard procedure. A spokesman for the Minneapolis Police Department said a formal review is always conducted in cases of officer-involved shootings.

Three people “with knowledge of the incident” told the Minneapolis Star Tribune that the responding officers pulled into the alley behind Damond’s home. The woman, wearing pajamas, approached the driver’s side door and was talking to the driver, the newspaper reported. The officer in the passenger seat then shot Damond through the driver’s side door, the three people told the newspaper.

When asked about the Star Tribune report, Jill Oliveira, spokeswoman for the BCA, said only that the investigation is in its early stages and that the state agency will provide information as it becomes available. The audio of the 911 call also is not available publicly.

State investigators say they will provide more information on the shooting after agents interview the officers involved – something that had not happened as of Monday afternoon, according to the BCA. Agents have requested interviews with the officers, who are working with their attorneys to schedule them, the state agency said.

Janei Harteau, the Minneapolis police chief, called the shooting “clearly a tragic death” and said she echoed the uncertainty reverberating through the community.

“I also want to assure you that I understand why so many people have so many questions at this point,” Harteau said in a statement Monday. “I have many of the same questions and that is why we immediately asked for an external and independent investigation into the officer-involved shooting death.”

The scant details have left city officials, and Damond’s family, friends and neighbors in Minneapolis shocked and confused about the circumstances that led to her death.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” Damond’s stepson-to-be, Zach, said softly and through tears. “I just want to have a conversation with that man.”

Asked what he would say to the police officer: “Why? Why did you do it? He has no idea the impact he had on thousands of people. I hope he thinks about that every day.”

As Zach Damond was out watering plants Monday, neighbors came by to hug him and offer help.

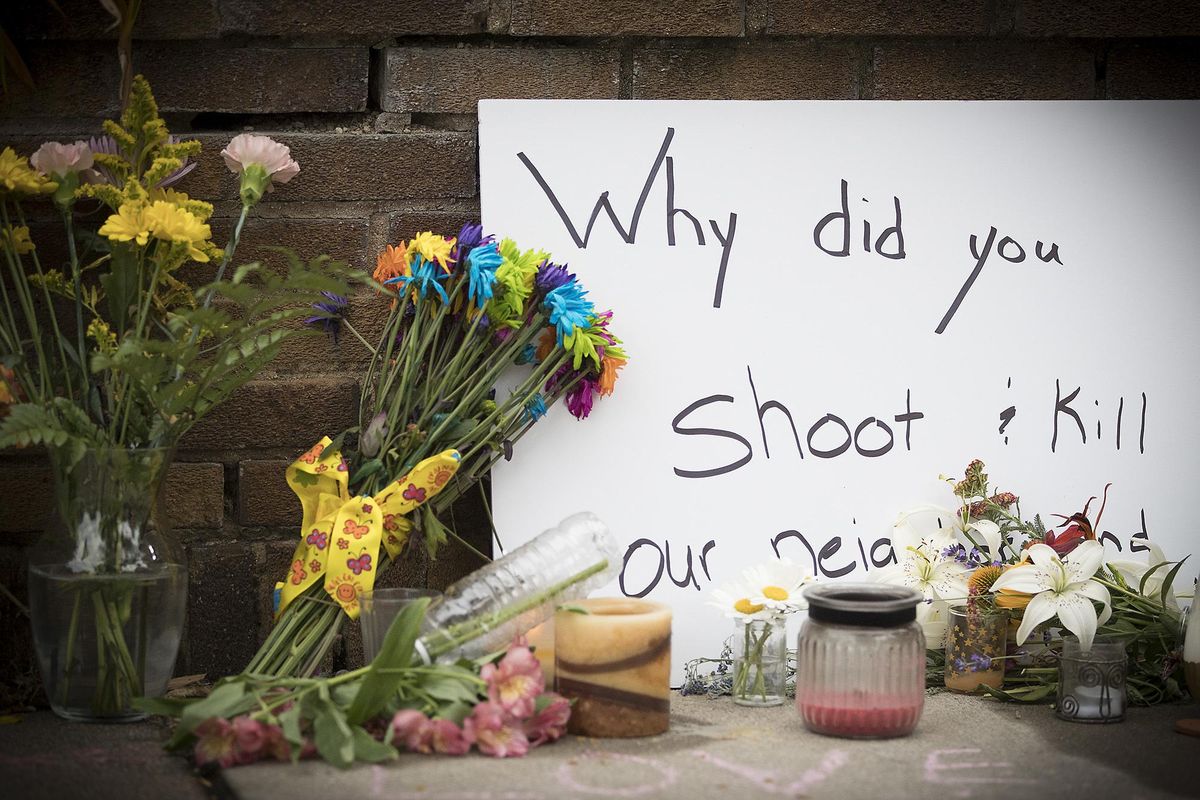

The end of the alley where Justine Damond was shot is covered in chalk messages. Flowers, candles, cards and photographs line a ledge along a backyard fence. A steady trickle of people have walked by, paying their respects, writing messages and leaving pamphlets for the community center where she worked.

The shooting over the weekend again has fueled distrust of law enforcement among Minneapolis residents. Lois and John Rafferty said they’d be reluctant to call the police for help and wouldn’t go outside to talk to them if they did call, noting that the shooting made no sense to them.

“How many people have to get shot?” John Rafferty said. “You can walk your dog at midnight around here. Minneapolis is not Syria.”

Bethany Bradley, of Women’s March Minnesota, said officials have not been transparent about the shooting and questioned why an audio recording of the 911 call has not been released.

“A woman should not call the police for help and end up dead. This should not have happened,” Bradley said. “This cannot happen in South Minneapolis. This cannot happen in North Minneapolis. This cannot happen in St. Paul. This cannot happen in the whole country. I’m angry.”

In a Facebook post Sunday night, Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges, who represented the neighborhood as a city council member, said she is “deeply disturbed” by Damond’s death and called on investigators to release more information.

“This is a tragedy – for the family, for a neighborhood I know well, and for our whole city… . There is a long road of healing ahead, and a lot of work remains to be done. I hope to help us along that path in any way I can,” Hodges said.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions was in Minneapolis on Monday giving a speech to an association of district attorneys, and Sessions emphasized the importance of law enforcement officers while saying that his department would prosecute any who break the law.

“We will aggressively prosecute federal or state officers who violate the civil rights of our citizens,” Sessions said, according to his prepared remarks. “But we will take care to never demean or offer unwarranted criticism of the honorable, brave, and professional law enforcement officers who protect us every day.”

Damond studied to be a veterinarian at the University of Sydney before moving to Minneapolis to be with her fiance, Don Damond. The couple planned to marry next month, but Justine Damond had already taken her fiance’s last name.

In a video posted to the Women’s March Minnesota Facebook page, Zach Damond railed against police-involved shootings in the United States.

“Basically, my mom’s dead because a police officer shot her for reasons I don’t know,” Zach Damond, Justine Damond’s stepson-to-be, said in a video posted to the Women’s March Minnesota Facebook page. “I demand answers. If anybody can help, just call the police and demand answers. I’m so done with all this violence.”

He added: “America sucks. These cops need to get trained differently. I need to move out of here.”

Don Damond was away on a business trip when the shooting occurred. His son, Zach, said his future stepmother heard a sound in the alley so she called police “and the cops showed up.”

“She was a very passionate woman, and she probably – she thought something bad is happening,” the 22-year-old said. “Next thing I know, they take my best friend’s life.”

Nancy Coune, office administrator for the Lake Harriet Spiritual Community Center, where Damond has worked as a Sunday speaker and meditation teacher for the past 2 1/2 years, described her as a “nonviolent” person.

“She’s not the type to provoke somebody. She would’ve maybe stepped in and helped somebody,” Coune told The Washington Post. “It’s quite unbelievable… . She was sweet. She was beautiful. She was kind. She had a bright light about her. Everybody wanted to be her friend, and this happened to her? In a very low-crime-rate neighborhood? Nobody understands.”

Coune said Damond and her fiance have both devoted their time to making people’s lives better and had talked about helping to improve race relations in Minneapolis. Don Damond is a volunteer at a local prison, where he teaches meditation, Coune said.

Despite Damond’s sudden death, Coune said she and others at the community center are not angry.

“Because that’s so opposite of what Justine was and what we actually teach and practice here,” she said.

In Australia, Damond’s friends and family are calling for a federal investigation into her death, News.com.au reported. A Justice Department spokesman declined to comment Monday.

“How someone teaching meditation and spreading love can be shot dead by police while in her pajamas is beyond comprehension,” Matt Omo, Damond’s friend, told the Australia Broadcasting Corporation.

Alisa Monaghan, another friend, said Damond moved to the United States to “follow her heart” and to find “new life,” the ABC reported.

Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said it is providing consular assistance to Damond’s family.

In a statement released by the agency, Damond’s family in Australia said: “This is a very difficult time for our family. We are trying to come to terms with this tragedy and to understand why this has happened. We will not make any further comment or statement and ask that you respect our privacy. Thank you.”

Damond’s personal and business website says she was a qualified yoga instructor, meditation teacher and a personal health and life coach.

Three mayoral candidates, Minneapolis NAACP officials and about 250 other friends, family and community members attended a vigil Sunday night where Damond was shot.

“Many of us who have been on the front lines have been warning the public, saying if they would do this to our fathers and our sons and our brothers and our sisters and our mothers, they will do it to you next,” said Nekima Levy-Pounds, one of the candidates and a civil rights attorney. “I really hope that this is a wake-up call for this community to stop allowing things to be divided on the lines of race and on the lines of socio-economic status.”

Damond is one of at least 524 people fatally shot by police in the United States this year, and the fifth such person in Minnesota, according to a Washington Post database tracking such deaths. Among people shot by police, she represents an outlier: Men make up the overwhelming majority of people fatally shot by officers. Damond is at least the 23rd woman fatally shot by an officer this year, accounting for just over 4 percent of all fatal police shootings.

Protests flared up last month when a jury acquitted Jeronimo Yanez, the officer who fatally shot Castile. The July 2016 shooting set off heated demonstrations that continued for weeks.

Just weeks before Castile’s death, federal authorities said they would not bring criminal charges in a November 2015 shooting involving Minneapolis police officers. Two officers fatally shot 24-year-old Jamar Clark, whose death sparked demonstrations. The prosecutor announced last year that the officers would not be charged, saying they believed he was trying to grab one of their guns.

A month before Castile’s death, the Justice Department said the officers would not face federal civil rights charges.

Clark’s death prompted a wave of protests outside a Minneapolis police station, demonstrations that eventually saw a burst of violence. Gunfire near the protests injured five demonstrators in November 2015, and prosecutors charged a group of men – not associated with the protests – in connection with the shootings. Last month, two men in that case pleaded guilty, while another had been sentenced to 15 years in prison.