Moving forward

COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. – This was the higher road, only amplified, and as such stands as a remarkably appropriate tribute to a life distinguished by grace and dignity in the face of intolerance and ignorance.

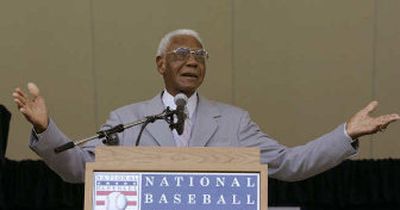

Buck O’Neil, at age 94, put aside his own immense disappointment Sunday afternoon as he stood on a podium outside the Clark Sports Center, a handful of blocks south of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

This was, after all, a celebration.

If his own exclusion made it bittersweet, as it had to be, O’Neil hid it well behind gentle good humor.

“All right, sit down,” he implored as everyone, including Hall of Fame members, rose to a standing ovation at his introduction.

O’Neil then praised and reminisced in the familiar soft lilt of his southern roots while helping to enshrine 17 players and executives from the Negro Leagues. Each one belonged in the Hall of Fame, he said. For each, the honor was long overdue.

And himself?

“This is quite an honor for me,” O’Neil insisted. “See, I played in the Negro Leagues … I’m proud to have been a Negro Leagues ballplayer.”

The honor is posthumous for each of the 17. The Negro Leagues ceased operation in 1960, though its scope began diminishing once Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947.

O’Neil is among a shrinking handful who form its living legacy, and his exhaustive efforts to promote its heritage stamped him as an obvious speaker–along with Robinson’s daughter, Sharon–at the induction ceremony.

Hall officials put those plans in place months ago, when it seemed certain O’Neil would be among the inductees. That changed in March, when a special committee deemed him unworthy of enshrinement.

O’Neil acknowledges disappointment but never considered reneging on his promise to speak at the ceremony.

“I’ve been a lot of places,” he said. “I’ve done a lot of things I really liked doing … but I’d rather be right here, right now, representing the people who helped build a bridge across the chasm of prejudice.”

“To have shared the podium with Buck today,” Sharon Robinson said, “is one of my greatest honors. Buck, I love you. Your contribution … we would not be here today without your contribution to baseball and to the Negro Leagues.”

The induction of 17 Negro Leagues personnel culminated a six-year project in which Major League Baseball funded research to produce a documented history as a preliminary step to compiling a list of candidates who merited consideration for induction.

That research produced 94 nominees. The field was then trimmed to 39 in November before a 12-member panel completed the project in March. 17 inductees were selected.

O’Neil was not among them.

But there was no bitterness as he spoke, just as there was none that day in March when he learned of the panel’s decision. Just as he has always insisted that no bitterness exists at being denied, because of his race, the opportunity to play in the big leagues.

“I never learned to hate,” O’Neil said.

He closed by getting everyone to join hands: Hall of Famers on stage, friends and family in the near seats and those beyond. All 11,000 in attendance.