Scientists see report as a start

The federal government and groups working to clean up mine waste from Idaho’s Silver Valley should use the newly released recommendations of a scientific panel to improve reclamation efforts and not let the group’s report go to waste, the panel’s chairman said Friday.

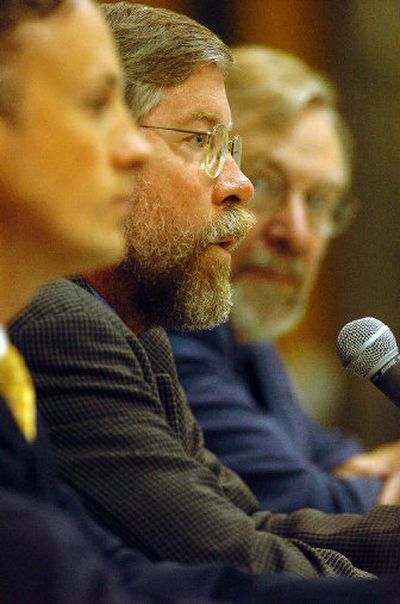

“We fully expect this will be reviewed, taken seriously and used by all the constituents,” David Tollerud, chairman of the National Academy of Sciences committee, told about 60 people gathered at North Idaho College Friday for an overview of the report.

Yet Tollerud, a University of Louisville professor of health, medicine and pharmacology, said the report is not intended to settle the ongoing controversies about the cleanup plan. Instead, people should use it as a “starting point” for how to address health and environmental issues in the Coeur d’Alene and Spokane river basins.

The report released Thursday finds that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s cleanup plan is based on “generally sound” scientific and technical principals and that the agency ought to expand its effort to protect residents and wildlife in the basin from the toxic legacy of 100 years of mining.

John Osborn, a Spokane doctor and Sierra Club member, was encouraged that the committee intends for its recommendations – including more emphasis on mitigating floods that can recontaminate cleaned up areas, mandatory blood testing for lead in young children, and increased review of zinc-tainted groundwater – to be taken seriously.

“Is this yet one more such report that ends up on the shelf collecting dust because it doesn’t fit with where the politics are?” Osborn asked.

Silver Valley resident Rog Hardy wanted to know about the future of the committee of 17 scientists that made three trips to the basin before reporting its findings, asking “Do you all go poof now?”

The committee is formally disbanded, but Tollerud said that if other issues or questions arise, the science academy could form another panel.

Some people said they would have liked more time to digest the 363-page report before the Coeur d’Alene meeting. Academy spokesman William Kearney said that panel members will remain dedicated to answering questions and interpreting the findings of the report for residents who live in the Silver Valley or anyone else with an interest.

Critics of the EPA’s $359 million cleanup plan, including Idaho’s congressional congregation, had requested the scientific review, saying the plan cost too much money, was based on shaky science and stigmatized the Silver Valley.

One of the report’s main emphases is that people, including those in the federal government, need to start thinking about all the things that might impact the cleanup process – from logging to building homes on the shores of Lake Coeur d’Alene – and not view Superfund in isolation.

“It’s a system; you can’t just deal with it in pieces,” said Tollerud.

Many environmentalists contend the cleanup also should focus on addressing the thousands of tons of toxic heavy metals that have been flushed into Lake Coeur d’Alene and the Spokane River. The report seemed to agree and expressed “substantial concerns” that the EPA is not going far enough.

Philip Cernera, remediation manager for the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, asked if an in-depth evaluation to document the extent of the contamination in the lake bed is needed before cleanup can be started.

Tollerud said that people “can’t ignore” the lake and that a study is needed, but that some aspects of a lake management plan can be developed now to “control the human effects of development.”

A lake management plan is one of the most contentious issues concerning the EPA’s work because the agency agreed not to insist on any cleanup of the approximately 77 million tons of metals-tainted mine sediments at the bottom of the lake. The agency instead wants to wait for Idaho and the Coeur d’Alene Tribe to develop an effective lake management plan to curtail nutrients and prevent more metals from mobilizing out of the sediments.

Rep. Dick Harwood, R-St. Maries, wanted to know when the EPA’s cleanup process will end.

“Are we going to be saddled with this agency for the rest of my life, my kids’ life and my kids’ kids’ life?” Harwood asked.

Tollerud said that it’s a difficult long-term decision for policy makers.

“I don’t have an answer,” he said.