What’s up in northeast Spokane? Not turnout

Northeast Spokane has an electoral problem that needs to be examined after the 2010 Census is complete. The problem isn’t who gets elected, but how few people do the electing.

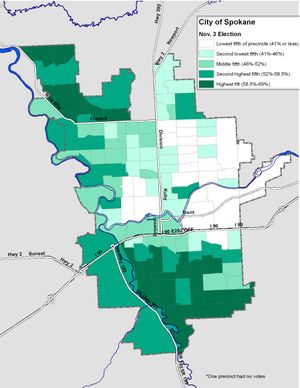

Results from this year’s general election follow a pattern evident in council elections since districts were drawn earlier this decade, and in legislative elections for decades before that. Northeast Spokane’s Council District 1, which shares many of the same precincts and voters and the state’s 3rd Legislative District, has significantly fewer voters than the neighboring districts. And the voters it has are less likely to cast ballots than other regions of the city and county.

That was particularly true this year. Although District 1 had a fairly contentious council race between Amber Waldref and Mike Fagan, the district – which is roughly everything north of I-90 and east of Division Street – had eight of the city’s 10 lowest turnout precincts, 17 of the bottom 20. District 1 also has about three registered voters for every four in the other two districts.

While this means that an individual District 1 voter has more impact on picking his or her councilmember, it also means that when grouped together with other voters on citywide issues, the area’s voters as a group have less impact than some in Indian Trails or the South Hill where registration and turnout is much heavier.

In this fall’s Spokane School Board races, for example, northeast Spokane voters went overwhelmingly for the challengers while south and the far northwest precincts backed incumbents.

Last March, District 81 passed its $288 million bond issue despite meager support in District 1. Bond issues need at least 60 percent approval, and most of northeast Spokane was below that, even though many precincts gave it a simple majority. District-wide, it passed with almost 63 percent of the vote on the strength of heavy margins and heavy turnout in the south and west precincts.

One could argue the power was reversed in this fall’s $33 million fire bond issue, which fell a few hundred votes shy of 60 percent citywide, despite getting supermajorities in most precincts south of I-90 and downtown. It failed to get simple majorities in nine precincts – seven of them in Council District 1. But the fire bond failure may be more a result of falling below 60 percent in the heavy turnout areas of far northwest Spokane. Supermajorities in those heavy voting precincts could have more than made up for the no votes in precincts south of Francis between Division and Market.

Spokane County Auditor Vicky Dalton said both political parties and other groups have tried for decades to increase registration and turnout in northeast and north central Spokane. Nothing has really worked, despite the fact that Washington is among the most accommodating of states for registering and getting ballots to voters.

It’s not likely to change, and it’s not a problem unique to Spokane, said Blaine Gavin, a Gonzaga University political science professor who has studied local politics for year: “That’s a problem you will find every place in the country with relative poverty and low education. If you create a district with poorer and less educated voters, you’re going to have lower turnout.”

The move from citywide council elections to districts was spurred in part by a lack of representation from northeast Spokane.

Districts are drawn based on total population, not voter registration or turnout statistics, and when these were set up in 2000, supporters and opponents agreed it was a standard way of looking at the city.

Redrawing the lines so the north side is divided horizontally and some of the northeast’s lightest voting precincts are put in with heavier voting precincts in the northwest won’t really solve the problem, Garvin said. If anything, that would mute the electoral voice of the low-income residents who do vote by mixing them in with more the more numerous affluent voters.

Turnout isn’t as big of a problem as true representation for different areas of the city, he argues. To get better representation, he suggests giving the city six districts, each with one council member, rather than the current three districts with two members. That would at least insure that smaller areas have equal voice on picking the council, and it may mean more voters would know something about the candidates they are choosing.

That would take a charter change. And charter changes are difficult. But recent history suggest passing a charter change is easier than increasing voter participation in northeast Spokane.