A long-lost document sheds light on the case of Chief Spokane Garry’s stolen land

A slab of grilled meat – the cut, texture and doneness all lost to history – arced over a fence and landed with a thud on a plot of ground on the flank of modern-day Beacon Hill in December 1883. Joseph Morscher, a German immigrant, had dark intentions; before tossing the muscled package he’d injected it with a deadly poison, strychnine.

“My children were going up to the fence where he threw the meat. I called them away,” Nellie Garry recalled in an 1891 interview. “My dogs went and eat the meat and three of them died that day.”

Scared for her life, Nellie Garry gathered her children and left the land, never to return. Her father, Chief Spokane Garry, was away angling for salmon on the Spokane River. By the time he’d returned, Morscher had taken up residence on the 15 acres Garry called home for more than 30 years, a home that hosted white dignitaries and power brokers of the day including Washington Territorial Gov. Isaac Stevens and the Rev. Henry Cowley.

Today, that land is choked with weeds, slabs of concrete and industrial trash. For decades, it was a camel farm. In the future, the land that Chief Spokane Garry once farmed is slated to be a 230-unit housing project nestled at the base of Beacon Hill, its appeal predicated on close-to-town beauty.

The sordid details of the land theft, which many thought were lost to history, are included in a new book by David Beine, a professor of intercultural studies at Great Northern University (the former Moody Bible Institute).

“I want people to know the horrific history of what really happened here in the stealing of Garry’s land by prominent founders and citizens of our city and leaders of our nation,” Beine said. “It is time to set the record straight.”

Beine’s book, “Whodunnit: The Continuing Case of Spokane Garry,” lays out those facts. The centerpiece of the 284-page book is a long-lost document Beine discovered in the National Archives detailing Garry’s yearslong attempt to get his land back and the coterie of Spokane power brokers that colluded against him.

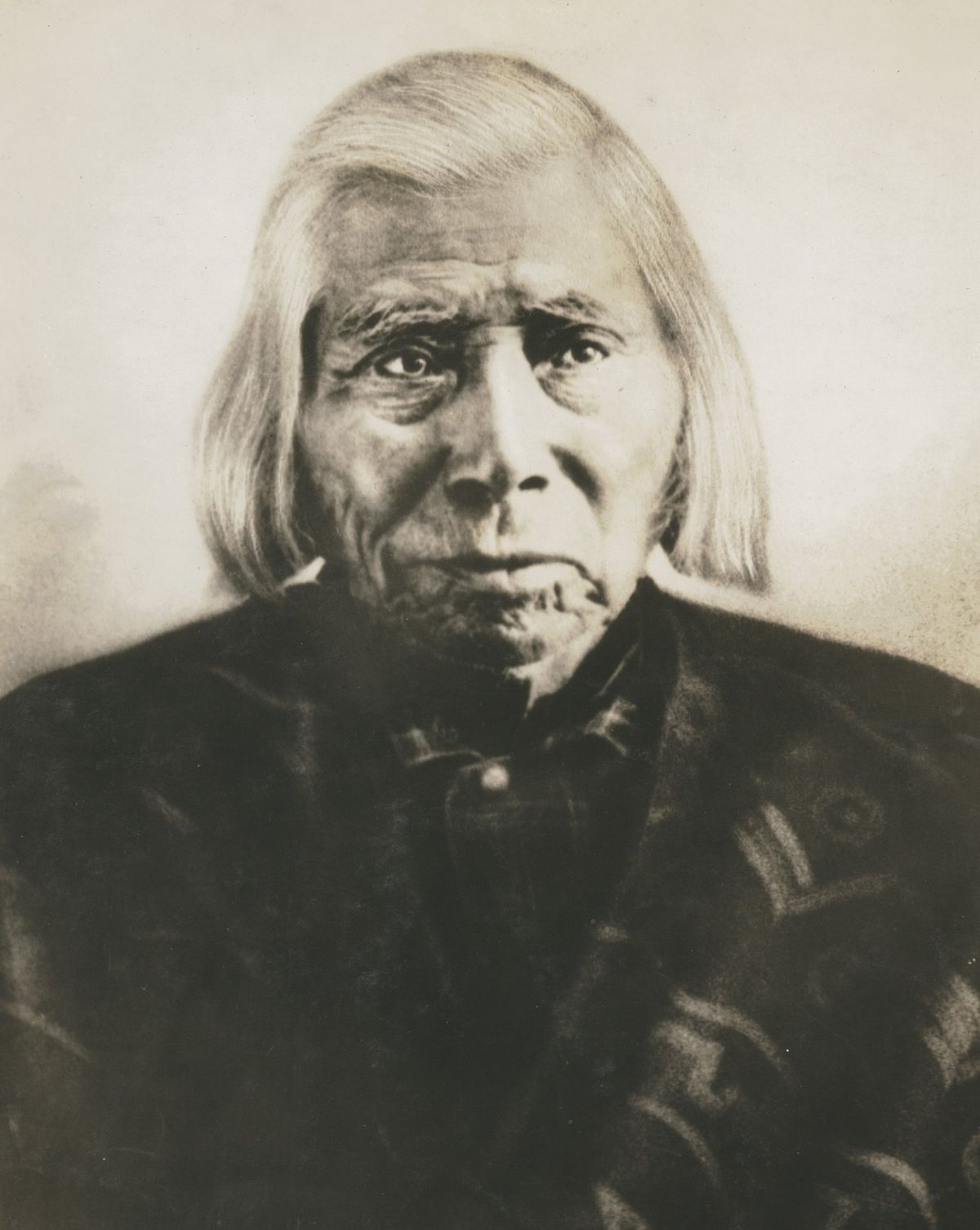

Born on the cusp of cataclysmic change, the details of Chief Spokane Garry’s life straddle two cultures and epochs. The son of a chief, he was born around 1811 and grew up near white traders in the Spokane area. Garry’s original Spokane Salish name was Slough-Keetcha, but at age 14 he became Spokane Garry after his father sent him to the Red River Settlement’s missionary school near present-day Winnipeg.

Founded by the Rev. John West, an Englishman, the goal of the school was, as he wrote in his 1825 memoir, “to establish the principle that the North-American Indian of these regions would part with his children, to be educated in white man’s knowledge and religion.” As part of that, Slough-Keetcha was given a new name, Spokane Garry, in honor of Nicholas Garry, a director of the Hudson Bay Company, which helped found the school.

It was the first such school in western Canada, and it did its job well. Garry learned to speak, read and write English and became a Christian. He returned to the Spokane area in 1830 at about the age of 19, at which point he became a leader, although he was likely not a chief in the formal sense, writes historian and journalist Jim Kershner.

Still, he was influential, and because he spoke English and French, he became a de facto spokesman for area tribes. He also taught farming techniques and, for a time, ran a school near modern-day Drumheller Springs in Spokane. And he was friendly with white leaders of the time, including George Simpson, a governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens.

By the 1850s, though, relations were strained as white settlers pushed into tribal lands. Garry advocated peace – urging his fellow Indians to avoid conflict and urging the whites to honor tribal rights – and sent eloquent and thoughtful letters.

“When you look at the red men, you think you have more heart, more sense, than these poor Indians,” Garry wrote to Stevens. “I think the difference between us and you Americans is in the clothing; the blood and the body are the same. Do you think that because your mother was white and theirs dark, that you are higher and better? … I do not think we are poor because we belong to another nation. If you take the Indians for men, treat them so now.”

Still, war broke out, culminating in General George Wright’s slaughter of 800 horses on the shores of the Spokane River, the destruction of wheat and other food supplies, and the hanging – after a 15-minute trial – of Qualchan, a Yakama subchief. The tribes signed a treaty, although for all intents and purposes it was surrender.

In 1881, the Spokane Indian Reservation was formed, although Garry refused to move there and continued to advocate for a reservation on either side of the Spokane River from the city of Spokane to Tum Tum.

But in his old age, at least, Garry had his land, a plot he’d farmed and lived on for 33 years. It was a place, he’d tell investigators, where he had grown wheat, oats, corn and potatoes every year. It was a place he chose to move onto, although he never formally filed for land ownership under the 1875 Indian Homesteading Act because he would have had to relinquish his tribal rights.

New insights into Chief Garry’s land

David Beine is an avuncular man with white hair, kind eyes and a knack for languages. He’s also a Christian with a keen sense of justice. As an anthropologist, Beine has spent nearly 30 years working with Indigenous groups in Nepal, trying to help them integrate into modern Nepalese life in a way that doesn’t destroy their traditional way of living. Throughout that time he taught and lived in Spokane and often took his students to sacred or important Native American sights in the area, including Garry’s former home on Beacon Hill.

In 2008, his interest in Garry’s land was piqued when The Inlander and The Spokesman-Review both published stories about Garry, each citing a different location for Garry’s land.

That put Beine on the case and he started to dig. Ultimately, his research supported the “orthodox view” of where Garry’s land was located, east of what is now Havana Street and between East Valley Springs Road and East Longfellow Avenue, but in that process he discovered a document filed by a U.S. special investigator appointed to adjudicate Garry’s land dispute. For decades, all that was known about Garry’s land case was that there had been a government hearing looking into the matter and that Garry, already dead at this point, had lost. All the documents were destroyed.

Not expecting to uncover anything new, Beine contacted the National Archives and asked for documents relating to Garry’s land dispute. An archivist there, Beine writes in his book, noticed that some of the letters about which Beine was asking were missing. She investigated and uncovered nearly 60 pages of testimony in the form of letters and interviews.

About half of those testimonies and interviews supported Garry’s claim to the 15 acres, Beine found. By the end of the investigation, the government -appointed investigator believed Garry and ruled in his favor and yet the final ruling was against Garry.

Why? Beine believes it was a coordinated effort on the part the new landowners and some of Spokane’s most influential citizens.

“While the preponderance of evidence in the contest should have protected Garry,” Beine writes, “in the end it seems to be undisclosed attitudes and falsely constructed technicalities that destroyed all hope for the return of his land.”

•••

When Garry returned from fishing and found his daughter gone and his land pilfered, he was “awful mad about it,” as he told an interviewer in 1891. But Garry was a great compromiser and peacemaker. A white friend convinced him not to confront the thief Morscher, urging him instead to plead his case with the federal government.

“The only thing I could see was for me to move to the falls where my women might earn something by washing,” he said. “A white man advised me not to quarrel with the Dutchman, as Washington (D.C.) would get my land back for me.”

And so the process began.

A special investigator was sent, at the request of the Department of the Interior.

By the time the investigator, John Skiles, arrived in 1891, Morscher had sold the land to Schuyler D. Doak. Doak had then turned around and sold the land to F. Lewis Clark, a Spokane business magnate and one of Spokane’s first millionaires, who himself disappeared in 1914.

Doak knew the land well, since he’d worked for Garry as a teenager.

Meanwhile, Garry moved first to Latah Creek, but was then driven from there, settling finally in Indian Canyon.

Garry had his supporters and the document Beine uncovered reflects that fact.

A number of prominent Spokane leaders testified against Garry, claiming he hadn’t lived on the land and had no real claim. Their testimony is oddly formulaic, Beine argues, suggesting some coordination. The group included James Glover, Spokane’s second mayor and the man who originally bought and platted Spokane.

“Garry never lived there for any length of time if at all,” he testified. “Garry has no desire or expectation to acquire title to the land in question.”

Yet Glover’s position didn’t convince Skiles, the investigator who saw a plot and called it fraud.

“From the facts established in the testimony, it would look as (Doak) was acting falsely to Spokane Garry during the times he worked for Garry and scheming to keep his land,” Skiles concluded, adding later, “it looks as if Doak first attained the confidence of Spokane Garry for his own benefit.”

He concluded that “according to the preponderance of evidence and the general impression of the whites, it would appear as if Spokane Garry was entitled to his claim.”

The investigator’s own conclusion, however, was ignored by higher-ups, and the government ruled against Garry.

•••

On Jan. 13, 1892, 130 years ago last week, Chief Garry died – landless – and was buried in a pauper’s grave. He was about 81 and “pining away on his couch of skins,” as one newspaper wrote.

•••

Displacement and dispossession are the historical facts of most land in Spokane and the U.S.

Because of Chief Garry’s stature, both in the 1800s and today, plus the paper trail uncovered by Beine, the details of this theft were documented in a way most weren’t.

“This small bit of land adjacent to the Beacon Hill project is important regionally and nationally as it tells the story of a not-so-proud era in the history of Spokane County, as well as the nation,” states a 2014 cultural survey of Garry’s former land done by the Spokane Tribe. “There are many thousands of these same stories in every tribe, and the wounds of descendants are still raw and unhealed due to the actions of white Anglo-Americans and the federal government, a legacy of unfulfilled and broken promises.”

For Garry’s direct descendants, Beine’s research has provided some closure.

“We now have documentation of how and why one of the most respected and distinguished Indian persons in the region could not attain and keep a simple claim for the land he lived on,” wrote Jeanne Givens, the great-great-great-granddaughter of Garry.

“From what was once confusing, we now gain deeper knowledge.”

With plans for developing that land inching forward, Beine hopes his research prompts, at the very least, reflection and remembrance.

He’s been in touch with Spokane City council member Lori Kinnear. The site doesn’t fall under the jurisdiction of Spokane’s historic preservation office, Kinnear said.

In November, the Spokane City Council extended a development agreement with the new owners of Garry’s former land.

It all means the new developers aren’t obligated to do anything with this history, Kinnear said.

Beine, however, would like to see a plaque commemorating Garry and detailing what happened.

“Perhaps there is no legal obligation,” Beine said. “But perhaps there is a moral obligation.”