Spokane brothers dominated souvenir market for decades with Hysterical Maps and decals

For three years, the Schade Brewery in downtown Spokane was called “de Gink.”

After a 15-year run producing upward of 40,000 barrels of beer a year, the brewery was first a victim of state prohibition in 1916, then national prohibition in 1920. Its owners tried brewing non-alcoholic beer and pop, but it didn’t last and the building was left vacant.

In 1930, the Great Depression hit and the brewery building was being used as a “hotel” for the homeless – an imitation of the first “Hotel de Gink” that opened in Seattle in 1915. This so-called hotel was organized by and for homeless people and provided food, haircuts and medical care. As its operation became more organized, the building became less of a squatting place and more of a sanctioned shelter, with the city providing assistance.

At the same time, two Spokane brothers named Jolly and Ott Lindgren were also feeling the effects of the economic calamity. Their sign-making and advertising business was struggling, and they needed a new product.

Jolly, the artist, had an idea.

“What this country needs now is something to put a smile on people’s face,” he said when still coming up with the plan.

He would illustrate an entertaining map of Spokane, stamped with the company’s name, address and phone number. They’d put a calendar in the corner, so this map – which was essentially an ad for the Lindgren Brothers company – would drum up some business, if luck would have it. The company’s new director of sales and customer relations, Ted Turner Jr., liked what he saw.

“Instead of a historical map, let’s make it a ‘Hysterical Map,’ ” Turner said.

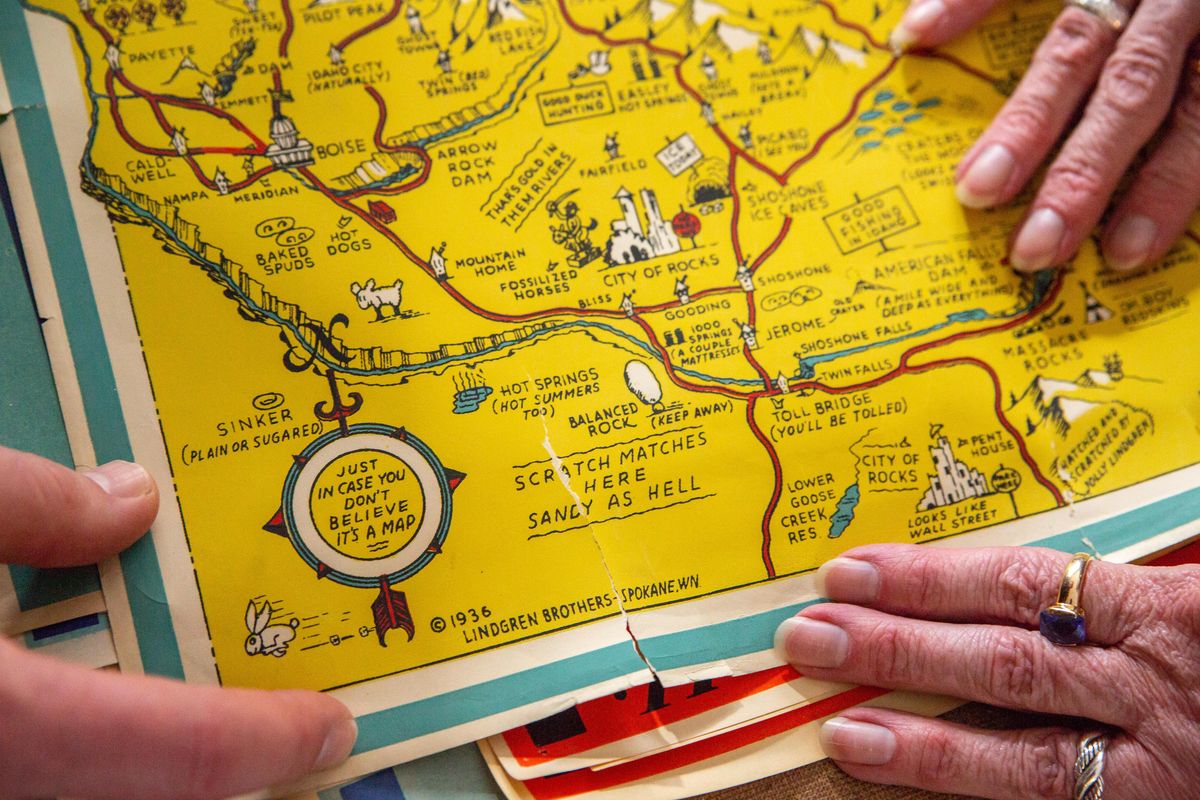

Thus was born the first “hysterical” map: a “slightly cockeyed” map of the “Spokane country.” The garish, five-toned map was filled with cartoon figures and wit, but little directional help. While it does well representing the layout of the Spokane area, it also has a blank zone in the northwest with the explanation, “This region is unknown as we have had no good reason for going over here.” Another note says, “Up this way lies Moran Prairie … but who cares.”

More importantly for the business, the Lindgrens used a “new but rather crude method” of making silk-screen stencils photographically. The effect was revolutionary to their trade and made it possible to reproduce fine details in both lettering and illustrations.

Seven printings of the map later, the brothers knew they’d struck gold. Over the next 20 or so years, the company would make maps of every U.S. state, national parks and many other notable tourist destinations. The company would go on to lead the charge in the national craze for decals, and even conceive and produce a humorous – if violent – “No Trespassing, Survivors Will Be Prosecuted” sign that was sold in thousands of department stores across the country.

But it all began with one map of Spokane. On it, just outside of a stack of downtown skyscrapers and beyond the blowing cloud of “Palouse Dust,” a familiar building stood alone and vibrantly red by the simply drawn railroad. It was labeled, in Jolly’s comic script, De Gink.

Becoming Jolly and Ott

Sara Lindgren is Ott’s only child, and her first job was taking orders for her father’s business. One of her earliest memories is visiting the three-story brick building that housed what was by then called the Lindgren-Turner Co.

Maps were pinned to the walls, the same maps she has in her collection. She’s aware that the company reached great heights in its time, only to dissipate and be remembered by few people in Spokane.

“That’s the way it goes,” she said.

She knows, better than most, that stories can be forgotten even while they’re hiding in plain sight.

Lindgren worked for The Spokesman-Review and Spokane Daily Chronicle newspaper reference library for 32 years, where she tended not only to the thousands of envelopes each containing dozens of clipped newspaper articles, but also to the envelope marked “Lindgren-Turner Co.”

Besides that, she’s something akin to the company’s unofficial archivist. In her collection, she has 20 original maps, numerous “King Size” map postcards, a board game, handwritten letters, an unpublished history of the company, a list of all the buildings the company occupied and more.

She’s the keeper of the flame for a company that began in 1928 and ended in 1972.

Hjalmer and Oscar Lindgren were born in Wisconsin, but moved to Sandpoint when they were children when their dad got transferred to the Humbird Lumber Co. sawmill there. Neither boy had middle names when they went to fight in World War I. But the Army required it, so both took on monikers that stuck with them for life. Hjalmer became Jolly, and Oscar became Ott.

As a child, Jolly was a gifted artist, and during his time in France during the war, he learned to make signs to communicate with the French he encountered.

After the war, Jolly landed in Oregon, where he used his sign-making skills for “an operator of moving picture theaters” who employed him to create “lobby displays, poster, banners window cards” and more, according to a history of the company written by Turner, who later became an owner with the brothers.

In 1927, Jolly moved to Spokane and rented space in the basement of the Clemmer Theater, now called the Bing Crosby Theater, and opened a commercial art studio. His first customer was the Clemmer, which paid him to make the displays and advertising. Soon enough, he was doing the same for the Pantages Theatre, which was located where the Parkade now sits, and other theaters and businesses.

With business booming, Jolly needed help, so he turned to his brother, Ott, who managed a lumberyard in Sandpoint. In 1928, the Lindgren Brothers was formed. Jolly was the artist, Ott was the businessman.

‘On the brink of evil times’

Every now and then in these early days, the brothers received an order for multiple copies of the same artwork. Through “trial, tribulation and error,” Turner wrote, the brothers became pioneers in screen printing.

“On a small scale and in small quarters, they began pioneering what was than a comparatively new idea – screen printing,” an article in the trade journal Screen Printing reported in February 1971.

It was a new technique that allowed for the reproduction of a multicolored image – exactly what the brothers needed. But they didn’t have the proper equipment, so they did what pioneers do and figured it out.

“They bought Swiss silk from a flour mill supply company,” Turner wrote in his history. “It was the silk bolting cloth used for sieves in flour mills. This was the screen for the stencils. Printing was accomplished by paint applied through the open mesh of the stencil with a rubber blade of a squeegee onto the material to be printed.”

There was still the matter of the appropriate paint to use.

“Ordinary house paint was all that was available,” Turner continued. “This required ‘filler’ ingredients to doctor it up and give it the right paste consistency. … Their own recipes called for starch, vinegar and kerosene to achieve proper drying, non blotting and sharp lines.”

In short, the brothers cracked the code of screen printing, and business was growing. The brothers moved into the second floor of the Lincoln First Federal Savings and Loan building at 120 N. Wall St. in downtown Spokane.

Two things happened around this time that defined the company until its final days. First, Turner joined the company as its traveling salesman. He would drive for months at a time, putting Lindgren Brothers’ wares in hands across the nation.

Second, the bottom fell out.

“By this time the ground swell from the 1929 stock market crash struck the west with sudden impact and the Great Depression was on the door steps of Spokane,” Turner wrote. “The Company was cliff hanging on the brink of evil times that were falling upon the nation.”

The art of yesteryear

On July 16, 1931, the Spokane Press ran a story on the brothers’ successful venture, not knowing that the company was months away from trouble – and reinvention.

“On the second floor of the National Savings & Loan building two brothers bend over easels, matching a color there, painting a little dab there, and laughing over a mutual joke or seriously discussing a problem in such technically artistic ideas as radiation, balance and rhythm,” the article began, noting that the brothers do “every form of display and sign work with the exception of billboards, and they ship their product to cities all over the west.”

But times were tough. The company’s landlords allowed them to cover some of the rent by making the bank window displays and ads. They made signs for the Diamond Ice and Fuel Company trucks, and got paid in part by coal to help heat their homes. Theaters paid for signs with free tickets, which the Lindgrens gave to friends and customers. They printed “bumper cards” – cards that had to be tied to car bumpers before adhesive became commonplace – for a successful gubernatorial candidate from Cheney.

“Long lean months trailed one another,” Turner wrote in his history. “At times heavy gloom cast depressing shade on hope and faith.”

Then, in late 1932, a turnaround. With the extra free time afforded by less business, the company experimented with a new method of printing that used photosensitive material. The result was “revolutionary,” Turner wrote, and allowed them to “reproduce fine detail lettering and illustrations,” and brought “unlimited potentials.”

The Lindgrens and Turner huddled: What product could they devise with the new method?

After graduating from the University of Idaho in 1926, Turner had sold calendars on commission. He pitched the idea to the brothers. A calendar “would carry their ad for a year and would be the most inexpensive method to introducing their new photographic stencil products.”

So Jolly drew up the first “hysterical” map, featuring the “Spokane country” with a little calendar stuck to its lower left corner.

Maybe the calendar would’ve done well anyway, but the company got a boost from Spokesman-Review columnist Stoddard King.

In a “Facetious Fragment” poem that ran on Jan. 2, 1933, King seems to have not known about the locally made calendar, and lamented the lack of art in the eight calendars he had for the year.

“The calendars have lost their charm,” the poem ends. “Where is the art of yesteryear?”

King’s mailbox was flooded with new calendars filled with art of “Fifth avenue after dark, … a bathing Girl and a Stag at eve.”

He also got one of the Lindgren maps, which was his favorite, as he wrote in another poem on Jan. 6, 1933:

“And, more amusing than all the others,

A map designed by the Lindgren Brothers,

Showing a cheerful, cock-eyed plan

Of the natural beauties of Spokane.”

The calendars were a hit. The company ran through three printings before realizing that it wasn’t really the calendar people wanted. Three more printings were done with the “Palouse Dust” taking the place of the calendar.

London to Yellowstone

Craig Clinton is a rare map collector and dealer based in Portland, where he owns oldimprints.com with his wife, Elisabeth Burdon. In 2011, he wrote an article about the Lindgren Brothers’ hysterical maps for the journal of the International Map Collectors’ Society.

In an interview this week, Clinton said pictorial maps like Jolly’s began with MacDonald Gill’s “Wonderground Map of London Town” from 1914, which was a promotion for the London Underground subway hung in every station.

The British Library says Gill’s map “presents a bird’s eye view of the capital peopled with characters from every walk of life making whimsical quips or puns about road or place names.” Examples from the map include men hurling hams in Hurlingham and a colorful serpent living in the Serpentine.”

“He’s top of the line in terms of the sort of work he did. That’s what really got the ball rolling,” Clinton said. “It quickly spread to this country.”

As Clinton said, the map, which was accurate for the “Tube” but also funny, was so popular that it spawned imitators.

In 1926, for the 150th anniversary celebration of the United States, the American imitators came. Boston, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., were made by Edwin Olsen and Blake Clark. “A Map of the Wondrous Isle of Manhattan” was created by C.V. Farrow.

When the Lindgrens struck upon their idea, Clinton said, they almost surely had seen one of these maps, if not Gill’s.

“What made them successful is they were able to place them at national parks,” he said.

Providing some mirth

Seeing the success of the first hysterical map, the company quickly created three more in 1933: one of the “Puget Sound country,” one for Mount Rainier National Park and one for Yellowstone National Park.

Turner, who had traveled widely for the John T. Little Sporting Goods Co. of Spokane, told his new bosses that souvenir dealers around Yellowstone always asked what he had for them to sell travelers. Now he had something.

One thousand maps of Yellowstone were printed on speculation. In the spring of 1933, Turner packed them in his car and went east. By the time he got to West Yellowstone, he was sold out, and dealers clamored for more.

Turner, showing his acumen as a salesman, told the Lindgrens that “it was reasonable to believe that Hysterical Maps would sell at most all National Parks and points of interest.”

The maps flowed, “hatched and scratched” and “made on purpose” by Jolly Lindgren. He made them for Glacier, Rocky Mountain, Grand Canyon, Bryce and Zion national parks, the Grand Coulee Dam, Death Valley, the Tetons and Jackson Hole, the Great Smoky Mountains and other tourist attractions.

They were just as silly as the first. A compass rose extolled its accuracy on one map, with the words, “This part is correct, so ’elp me.” The map of Rainier said the landscape was “430 square miles of ‘UP.’ ” Death Valley had a road that said, “This road is a lousy road.”

The decision to focus on tourism was fortuitous. Though the economy remained sluggish, tourism wasn’t affected, thanks in part to the Works Progress Administration building new roads to the nation’s parks.

“Further aids to travel were provided through road maps distributed without charge by oil companies in their pursuit of an expanded clientele at the gas pump,” Clinton wrote in the journal article. The maps linked auto travel with good living. As James Akerman, a cartography historian, wrote in the journal Cartography and Geographic Information Science, the promotional maps of the 1920s and ’30s “associated automobile tourism and the consumption of automobile goods and services with refinement, patriotism, family responsibility, and other positive values.”

Business roared, and the company was a national success.

On Sept. 15, 1940, the Spokesman ran article headlined: “ ‘Hysterical Maps’ Are Popular.”

“ ‘Hysterical Maps,’ born of depression and reared in ironical defiance of slack business, have attained national recognition,” the article read. “They can now be listed with the Spokane-made products that circulate throughout the United States. They are ‘cockeyed maps,’ ‘drawn in broken English,’ by Jolly Lindgren, geographically correct but amusingly exaggerated.”

The article reported on the company moving to bigger and bigger spaces to accommodate their growth, first to the Realty Building on Riverside, which is now owned by Catholic Charities and is operated as low-income housing, then to a building on East Sprague Avenue and Grant Street that was purchased by Avista last year.

“These maps reproduced in four colors say things on them that regular map-makers don’t dare to say and are rhetorically atrocious. But people like them,” the article read, noting that the maps “provide some mirth.”

The future looked bright. Then war came.

Decal-mania

Over the course of World War II, more than 16 million Americans served in the U.S. armed forces. Two of those men were Ott Lindgren, a captain in the Army Engineer Corps Reserve, and Ted Turner, a captain in the Army Infantry Reserve.

Jolly, who was 46 years old when Pearl Harbor was attacked, stayed behind to run the business, but the loss of two-thirds of the managerial manpower effectively squelched the map business.

“These were tough times for him,” Turner wrote. “Manpower was short as well as normal supplies.”

But the war wouldn’t stop the business. In 1946, with Turner and the Lindgrens back together, they struck upon another souvenir idea: decals.

On Oct. 28, 1948, the Chronicle ran a profile on this new side of the business, which had propelled the company to a new three-story home on West Broadway Avenue and North Lincoln Street.

“If you buy a souvenir decal while vacationing next year in Florida or just about any other part of the country, chances are you’ll discover it was made in Spokane,” it began. “Few persons realize it, but Spokane rapidly is becoming the souvenir decal-manufacturing center of the United States, thanks to the Lindgren Brothers.”

The idea was simple. Jolly would continue illustrating the nation’s tourist spots, sometimes drawing characters from the maps, other times creating something new. His first decal, perhaps unsurprisingly, was of Old Faithful in Yellowstone.

“Jolly Lindgren, the artist of the partnership, drew three or four designs advertising Yellowstone national park. Yellowstone took all the brothers could produce that year and sold 60,000 to vacationers,” the article said.

The next year, in 1947, the company sold 300,000 decals of Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Glacier, Grand Coulee and other locales. At the beginning of the 1948 tourist season, the company had 300 different designs for its decals “and retailers from Florida to Alaska were selling the Spokane-made stickers.”

By the time the article was written, the company had sold 1.5 million souvenir decals, and they expected to see even more business the following year. The goal was to have 600 unique decals. Turner said the market “hasn’t been scratched,” noting that every third person who entered Yellowstone that year bought one of their decals.

In 1949, according to a Chronicle article written 20 years later, the company had its best year ever, and produced 10 million decals. The same year, Turner became a full partner and the company was renamed the Lindgren-Turner Co. By this time, thanks in large part to Turner’s travels, the company worked with 35 distributors who placed the decals in 25,000 souvenir shops across the country.

“Everywhere they all wanted something distinctive of their own locality,” Turner told the Spokesman in 1950. “We had been making some commercial decals. Souvenir decals seemed a natural fit.”

The same article that quoted Turner described the decal-making process: “Jolly Lindgren will get a brainstorm – or some souvenir dealer will send him a rough sketch of what he wants. He sits down at the drawing board and turns out a pen and ink sketch. This is photographed. Jolly hand-colors the print and hands the print and the negative over to production manager Harvey Moore. Moore cuts out the five different color stencils by hand, transfers them to silk screens. Then the printing begins. Extra coats of colorless paint are put on the decals for strength. The final coat is glue.”

The quick process occasionally led to mistakes, but only once did the company get a “kickback,” or complaint.

A “curio dealer in Kansas” wanted a decal featuring a buffalo and a “Kansas” label. Jolly had done a buffalo once before, for a decal of Lake Louise, in Canada. While removing the buffalo, “the boys” forgot to remove some Canadian background. Thousands were printed, and a letter came.

“Mountains – in Kansas?” was all it said.

‘No Trespassing, Survivors will be Prosecuted’

Again, the passage of time had different ideas about the company’s future. In 1952, Jolly was “taken by death,” as the Spokesman reported. At 57, he died of a heart attack while visiting his daughter in Boise.

“Vacationing Spokanites have traveled thousands of miles to purchase a ‘made in Spokane’ decal to brighten an auto window,” his obituary read.

His death, though, didn’t bring an end to the business. Two more hysterical maps were made, these drawn by William Terao, who had been forcibly relocated to an internment camp in Idaho during the war simply due to his Japanese heritage. After the war, Terao was hired by the Lindgrens and eventually became head of the company’s art department.

Terao also founded the Spokane Buddhist Temple with his brother, and was its spiritual leader for decades.

By 1960, the decal business was “saturated,” according to Turner, and the company again turned to a new product and, again, found success, this time for the last time.

“Ott Lindgren came in one day with a ‘chuckle item’ that he encountered,” Turner wrote. “The wording was ‘No Trespassing, Violators will be Persecuted.’ ”

Soon enough, the wording changed to become “No Trespassing, Survivors will be Prosecuted” and the company sold them “readily.” It began with the local J.J. Newberry’s department store, which sold them. Then the local Sprouse-Reitz ordered some. Then Woolworth’s ordered some – for all of its 2,228 stores nationwide.

Within four years, the company reported that it had produced 1 million of the signs. It along with the company’s 40 other stock signs – Apartment for Rent, No Parking, No Peddlers – were done with bright, fluorescent paint.

“These radiant signs are what put us in the national market place,” Ott Lindgren said, perhaps forgetting some history. “It is the first upgrading of the lowly ‘Beware of Dog’ type sign since printing came into existence.”

Spreading laughs

Ott wouldn’t enjoy the fruits of his labor much longer. In April 1967, he died at the age of 74 at his home, leaving Turner as the remaining member of the group that worked on the first hysterical map 35 years before.

For a man who rode horses to elementary school outside of Nampa, Idaho, who graduated from college with a degree in psychology with an idea to become a writer, who wrote a paper called “Progeneration and Practice of Present Day Cursing” for a philosophy class, his work as a salesman at a printing company may not have been his ideal career.

But he was good at it and put his all into it, said his daughter, Martha Turner Nail, who lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“He was a wonderful salesman. He was very low key. You would hardly know you bought something,” Nail said. “He would be gone at least six weeks in the winter time because he would be going around to all his jobbers. He traveled the whole United States.”

Nail’s earliest memories of the business are of its location on Broadway, across the street from the newly renovated old Wonder Bread factory. At the time, the factory pumped out bread, and the neighboring Rainier Brewery made beer. Combined with the strong lacquer scent from her father’s company, the young Nail’s nose is what brings her back to that time.

“On one corner was a brewery, on the other corner a bakery. There were all the odors,” she said.

Nail’s description of Turner is of a kind and outgoing man, involved in his church and rotary, devoted to his wife, Virginia, and willing to act in skits with his only child. He wrote letters to his parents every week, and kept a list of the birds he had seen through his life. The way Nail describes her father, he never stopped.

“He was very much into helping others. He always had somebody he was helping,” she said.

But in February 1971, just four years after Ott’s death, Turner sold the company to the Los Angeles-based Emblem Manufacturing Co. At the time the company had 50 employees and was selling about $750,000 worth of decals, ski posters, felt pennants, parking permits and other items a year.

Three years later, he and his wife moved to New Mexico to be close to their daughter. In his retirement, he still kept busy, Nail said, and wrote the history of the Lindgren-Turner company.

In 1989, Turner died at 87. But well before then, when the company was in the rush of its third and final hurrah with its “No Trespassing” sign, he told the Spokesman why he stayed with the Lindgrens so long, revealing a bit about what drove him.

“This business is fun,” he said. “Spokane has demonstrated here that a laugh can spread into a nationally accepted product more than once.”