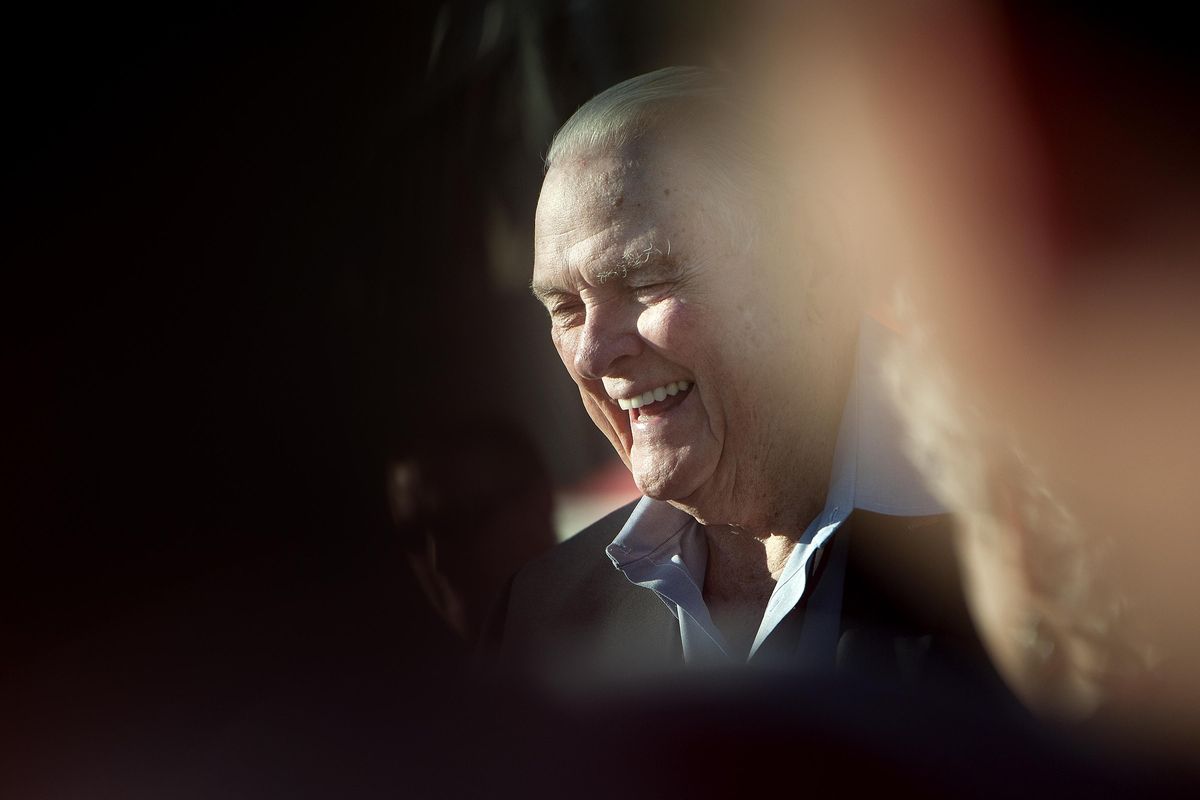

Legendary broadcaster Keith Jackson, ‘the soundtrack of Saturday afternoons in the autumn,’ dies at age 89

PULLMAN – With a voice that was identifiable to fans from one coast to the other, a spirit that nearly every one of his viewers could connect with and a southern charm that gave his telecasts a special comfort, Keith Jackson for the better part of five decades established himself as one of college football’s beloved characters. He was adored on a national spectrum, but few places embraced the sportscasting giant like Pullman and Washington State University.

And even as Jackson’s legend grew, the small college town in the middle of the wheat fields never felt too far away.

“I’m delighted to come back home, and my thoughts are, who wouldn’t want to go to school here?” Jackson told Cougars radio broadcaster Bob Robertson before a 2014 game in Pullman.

Jackson, a 1954 graduate of WSU’s Edward R. Murrow College of Communication who was known as “the voice of college football” to some and “Mr. College Football” to others, died around 11:30 Friday night at the age of 89. The cause of death wasn’t specified, but Jackson died in his Sherman Oaks, California, home “with those who loved him around him,” according to longtime friend and Washington State Association of Broadcasters President Keith Shipman.

Throughout a career that spanned 52 years, Jackson’s voice accompanied the telecast of many of the country’s – and world’s – classic sporting events. He worked 15 Rose Bowls, 16 Sugar Bowls, 10 different Olympic Games – both Summer and Winter – the World Series and Monday Night Football.

“I remember vividly watching the 1972 Munich Olympic Games and his call of Mark Spitz’s seven gold medals,” Shipman said. “And that’s what inspired me to pursue my dream of becoming a sportscaster. … And then while in Pullman, I was fortunate enough to earn the Keith Jackson Scholarship and that helped put me through school. Little did I know I would become a friend and he would become one of my most profound mentors during my career.”

Those who didn’t know Jackson on such a personal level still felt an intimate connection to one of the industry’s all-time greats.

Because of Jackson, Michigan’s enormous football stadium is “the Big House” and the Rose Bowl is “The Grandaddy of them All.” Jackson coined the phrase “Whoa Nellie” – an homage to his father and Roopville, Georgia, upbringing – and expressions such as “Fum-BULL,” “Hold the phooooonne!” and “Big uglies” – referring to a team’s offensive linemen – became familiar staples of Jackon’s ABC broadcasts.

“He was the soundtrack of Saturday afternoons every autumn,” Shipman said, “and still 10, 11 years later I miss that sound emanating from fall.”

Jackson’s specialty was college football, but he possessed the rare gifts of range and breadth, so he didn’t limit his work to Saturday afternoons in the fall. Toward the beginning of his career, Jackson was covering Seafair hydroplane races for KOMO TV in Seattle. Later on, he was ringside when he interviewed Fidel Castro at an amateur boxing championship in Cuba.

In 1958, while working for KOMO, he traveled to Moscow, Russia, for a University of Washington rowing event. Jackson historically – and controversially – became the first American to perform a live sports broadcast in the Soviet Union.

But a career that had plenty of pit stops, taking Jackson from Pasadena, California, to Munich, Germany – and 33 countries in total, he’s claimed – was rooted in Pullman.

“Every time you see him on TV doing his thing, he’ll always find some way, some way on the television broadcast to mention Washington State,” said Pullman Mayor and longtime voice of the Cougars Glenn Johnson. “… The best part about it, yes you leave, you have a fantastic career but you always stay back home and you’re always taking care of Pullman.”

The wandering grain fields of the Palouse are where Jackson obtained his undergraduate degree and met his wife of 63 years, Turi Ann. In 2014, WSU invited the couple back to Pullman to dedicate Keith Jackson Hall in Jackson’s honor. That was just a small way of repaying someone who regularly opened his checkbook to give to his alma mater, donating more than $1 million since receiving his diploma in ’54.

“You know when we get old enough to look back and reflect upon our experiences and achievements, I guess most of us can recall a special teacher, a coach, a particular class in school or a place where we’ve lived that left a lasting impression on us,” Jackson once said. “All these kind of things come tumbling back through the mind and memory when we recall our years at WSU.”

Jackson was generous to the Murrow College not only with his money, but his time. He organized a sports-specific symposium, Johnson recalled, and “brought in some of the big ABC talent, leaders in sports … had them all here, put a great symposium together.”

“He’s just a nice guy,” the Pullman mayor said. “He means a lot to this community.”

Jackson’s broadcasting career began in 1952 when he called a Washington State-Stanford football game for the school’s radio station. Seldom did his tenure with ABC bring Jackson back to Pullman, but he did return many years later for a 2003 game against UCLA.

Shipman has distinct memories of the game. He’d brought his son Greg along and the two had spent the day touring the WSU campus.

“He was clad in crimson and gray from head to toe … we were waiting in line at the will call window, my son tugged on my arm and looked up at me and said, ‘Dad, I am so going to Washington State when I grow up,’” Shipman said. “I was so proud at the moment and right behind me, I hear the distinctive voice of college football say, ‘Well, we’re going to have to get him academically eligible then.’ And I turn around and Keith and Dan Fouts are laughing.”

Jackson, at the time, was a spokesperson for Gatorade and appeared regularly in commercials for the popular sports drink. That’s how Shipman’s son recognized the sportscaster.

“My son looked up at Keith and said, ‘I know you, you’re the Gatorade guy,’” recalled Shipman. “Keith leaned over to me and whispered … he said, ‘For 50 years I’ve been the voice of college football and now I’m the (expletive) Gatorade guy.’ From that moment on, whenever we talk, he always asks ‘So how’s the little Gatorade guy doing?’”

The Jackson that college football loyalists saw and heard was a down-home southerner who, much like ex-Los Angeles Dodgers sportscasting legend Vin Scully, had the ability to let his broadcasts breathe.

“Silence is an interesting thing,” Jackson said. “A lot of things go on when things are quiet. You don’t have to fill every moment with a syllable.”

“The thing I admire most about him is he treated the viewer or the listener as if they had a brain,” Shipman said. “He allowed you to digest the information, use it to formulate your opinion. … But he never told you what to think.”

Jackson subscribed to a simple philosophy – “Amplify, clarify, punctuate and let the viewer draw their own conclusion” – and used the model to capture radio and TV audiences for half of a century.

Jackson famously stood up Bear Bryant when the Hall of Fame Alabama coach made him wait nearly an hour for a postgame interview.

“(Bear) came and stepped out of the little crowd and said, ‘Do you want to see me?’” Jackson recalled. “And I said, “Not anymore coach. We’ll catch you next time.’”

He signed off for the final time in 2006 at the USC-Texas national championship football game in Pasadena.

“Fourth and 5, the national championship on the line right here,” Jackson said, depicting the scene as Longhorns quarterback Vince Young came up to the line of scrimmage with UT trailing by five points inside the final minute. “He’s going for the corner … he’s got it!”

One of Jackson’s signature pauses followed before the famous voice returned to the airwaves: “Vince. Young. Scores.”

Jackson is survived by his wife, his three children, Melanie Ann, Lindsey and Christopher, and his three grandchildren.