Spokane’s first pro ball team also its first champ

Although Spokane has been winning professional baseball championships for more than a century, who could have guessed that its very first team, quite possibly its most interesting, also ranks with its most successful?

Since 1890, some exceptional players and many excellent ones have represented this city. So have a few eccentrics, rascals, entrepreneurs and criminals. But, in 1890, the inaugural band of diamond mercenaries, led by a flamboyant promoter and built around a legend or two and some drunkards, brought home a pennant.

Pro ball came to Spokane 125 years and two weeks ago today.

Inland Northwest fans have seen such early 20th-century stars as Hall of Fame members Stan Coveleski and George Kelly, as well as the trio of Earl Sheely, Ken Williams and the bon vivant Dutch Ruether that carried the Indians to the 1916 title. Minor-league immortal Smead Jolley had a Triple Crown season here in 1940.

Starting in 1958, Triple-A baseball boosted position-playing stars like Tommy Davis, Ron Fairly, Willie Davis, Frank Howard, Steve Garvey, Bill Buckner and Bill Madlock into the major leagues. Bill Singer, Charlie Hough and, briefly, Hall of Fame members Don Sutton and Hoyt Wilhelm pitched here. Irrepressible Tom Lasorda, who managed the brilliant 1970 Indians, was bound for the Hall of Fame.

And this era’s Northwest League teams have produced current standouts Zach Greinke, Carlos Beltran, Ian Kinsler and Chris Davis. Spokane won four straight titles in the late 1980s, one under current San Francisco Giants skipper Bruce Bochy, who’s destined for Cooperstown himself.

Game comes to Spokane

All told, this city has fielded 20 championship teams.

None of them had a leader quite like John Barnes, or a batting star to match “Piggy” Ward, a pitcher as productive as “Happy” Jack Huston or one as ill-behaved as George Borchers. No player has been as entrepreneurial as Abner Powell. And, supported by other minor-league mainstays, the 1890 Spokanes helped the Pacific Northwest League bring the national pastime to this part of the country.

Even though the Victorian era had been the age of ballyhoo in baseball, Barnes was a singular bundle of self-confidence, who barely balanced ambition, braggadocio and accomplishment. He said he held a national broad-jump record and that he had run foot races for money. Eventually, he said he had sparred with champions John L. Sullivan, Bob Fitzsimmons and Jim Jeffries, wrestled with Strangler Ed Lewis and learned several languages. And, although news traveled slowly in those days, many of his claims may have been true.

Barnes, born in Ireland, came to the U.S. as a child and, as a young adult, moved to Minnesota, where he tried his hand at baseball by directing St. Paul’s franchise in the fledging Northwestern League. In the 1880s, the Northwest was thought of as the region more or less bounded by the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. The Pacific Northwest was out there, you know, where the Northern Pacific railroad went.

If you believe what Barnes said – he liked hanging around reporters – baseball interfered with his other enterprises, so he gave it up after a few years. But, by then, he didn’t need the money. An uncle had died in Ireland and left him the modern-day equivalent of almost $3 million.

Meanwhile, this region’s baseball boosters, their young cities invigorated by the new transcontinental railroad, decided they needed a baseball league. The rail company, seeking both tourists and immigrants, thought that was a fine idea and, he said, engaged Barnes in early 1890. So, in the professional sense, Barnes became the father of baseball in the Pacific Northwest.

Each city’s backers put up $10,000. Spokane businessmen raised the money in four hours. Then, Barnes, so pleased that he then reserved management of Spokane’s team for himself, recruited investors in Portland, Tacoma and Seattle.

Those days, manager meant business manager. A playing captain directed matters on the field. Barnes picked Fred Jevne, who had played outfield for him in St. Paul. Most professional players were working-class sons of Irish or German immigrants. Many had little education. Rough play, coarse language and alcoholism were common. Although team nicknames were not, sniggering West Side newsmen sometimes called the outfit from this city, still officially Spokane Falls, Bunchgrassers.

The local field, referred to as Twickenham Park, had a wooden grandstand built the previous July in Twickenham Addition, John Sherwood’s project developed on land later utilized by Fort George Wright and largely occupied today by Spokane Falls Community College. When the development, far from downtown, fell flat, the stands were dismantled and reassembled on Sherwood property near the northwest corner of Boone Avenue and A Street. Admission was 25 cents. For an additional quarter, fans could sit in the covered grandstand.

The first season

The inaugural season began on Saturday, May 3, with Spokane playing host to Portland. Game time was 3:45 p.m., and it was hot, 87 degrees, a record that stood until 1992. The locals wore black knickers, stockings and caps with white shirts. A shield over the left breast spelled out Spokane in black letters. After a parade through the city core, players, in uniform, and most of the 1,662 fans rode to the field on Sherwood’s short-lived Spokane Cable Railway.

Gus Klopf, a right-hander from Milwaukee, took the mound for Spokane, which in the optional fashion of the time, elected to bat first. The Oregon city’s best homegrown player, pitcher Tom Parrott, drove in the winning run to give Portland an 8-7 victory in 11 innings.

The next day, catcher E.L. “Sam” Mills, who had played for Barnes at St. Paul, hit the first home run, and Spokane gained its first win, 14-8. In the fifth inning, Jevne, disputing a strike call, punched umpire W.A. Cragin in the neck. Cragin fined him $10 on the spot, and Barnes, no fan of rowdy play, upped it to $100, almost half a month’s salary.

Seattle came to town for the second series. After each team won twice, Spokane finished the homestand by facing Tacoma (7-1), the league leader. The locals won three of the four games and tied the race after scoring nine times without a hit in the second inning of the poorly played finale, which it won 19-15.

After a road trip that included visits to each of its three rivals, Spokane came home with a 14-12 record. By then, the Texas League, dominated by star-studded Galveston, had collapsed. Barnes, who apparently had advance knowledge, signed five of its best players: hitting star Frank “Piggy” Ward, pitching ace “Happy” Jack Huston, roly poly outfielder Mark Polhemus, Tom “Beezy” McGuirk and William “Kid” Peeples.

Those five men transformed Spokane into a different team and made their debut when the rain-delayed second homestand began on Saturday, June 21.

Klopf was now sidelined by malaria. So Huston stepped in and started a series sweep. When he defeated Seattle the following Saturday, Spokane took over first place.

On July 2, outfielder Tom Turner showed up late and in street clothes, elbowing his way into the grandstand with Jevne in tow. Both of them were drunk. Team president Tom Jefferson told them to pay a fine. Turner refused. When Jefferson repeated his order, Turner said “I’ll see you tonight and I’ll punch the head off you.”

Tucker apologized the next day, agreed to a fine and promised to avoid both liquor and Jevne. Barnes suspended Jevne, who didn’t apologize. On Friday, Huston beat Portland to open a Fourth of July doubleheader and when he won again on Saturday and Sunday, he had seven victories and one loss in little more than two weeks.

Spokane began a road trip with two wins at Tacoma for 11 in the last 13 games, and its lead began to widen.

Before the third homestand on July 23, the original Monroe Street Bridge, built of wood, burned down, cutting service on the cable-car line. By the time play resumed, Barnes had made his final two major roster changes, replacing Klopf and Jevne with Abner Powell, the player-manager at Hamilton, Ontario, and George Borchers. Powell, a teetotaling outfielder who would become known as the father of baseball in New Orleans, became available when the International League folded. Portland had released Borchers for drunkenness.

After skipping out on Stockton in 1889, Borchers had joined that California League team in early 1890 and he pitched well until the day he showed up on horseback, in uniform and drunk. Teammates chipped in to pay his fine, but Borchers spent the money on a rampage that ended in a jail cell. Portland manager Henry Harris then gave him a chance but gave up after fewer than seven weeks.

Barnes, who recalled in a 1925 Seattle Post-Intelligencer memoir that “Borchers was a star hurler when he was not throwing his arm across a bar,” had a solution. According to a story in The Sporting Life, chief rival to The Sporting News, the Spokane manager provided his fractious pitcher with room, board and clothing but no cash until the end of the season, telling him that, if he were caught drinking, he would forfeit all of his pay.

Although Borchers walked nine in his first start, that was his new team’s only defeat in more a week. After completing a sweep of Tacoma on Aug. 3, the Spokanes (33-21) had won eight of their last 10 starts. Then, they won five more for a 10-game winning streak. And when they began their next road trip by taking three out of five at Seattle, the pennant race was over. By Aug. 31, Spokane (46-25) headed home with 19 victories in 25 games and a nine-game lead.

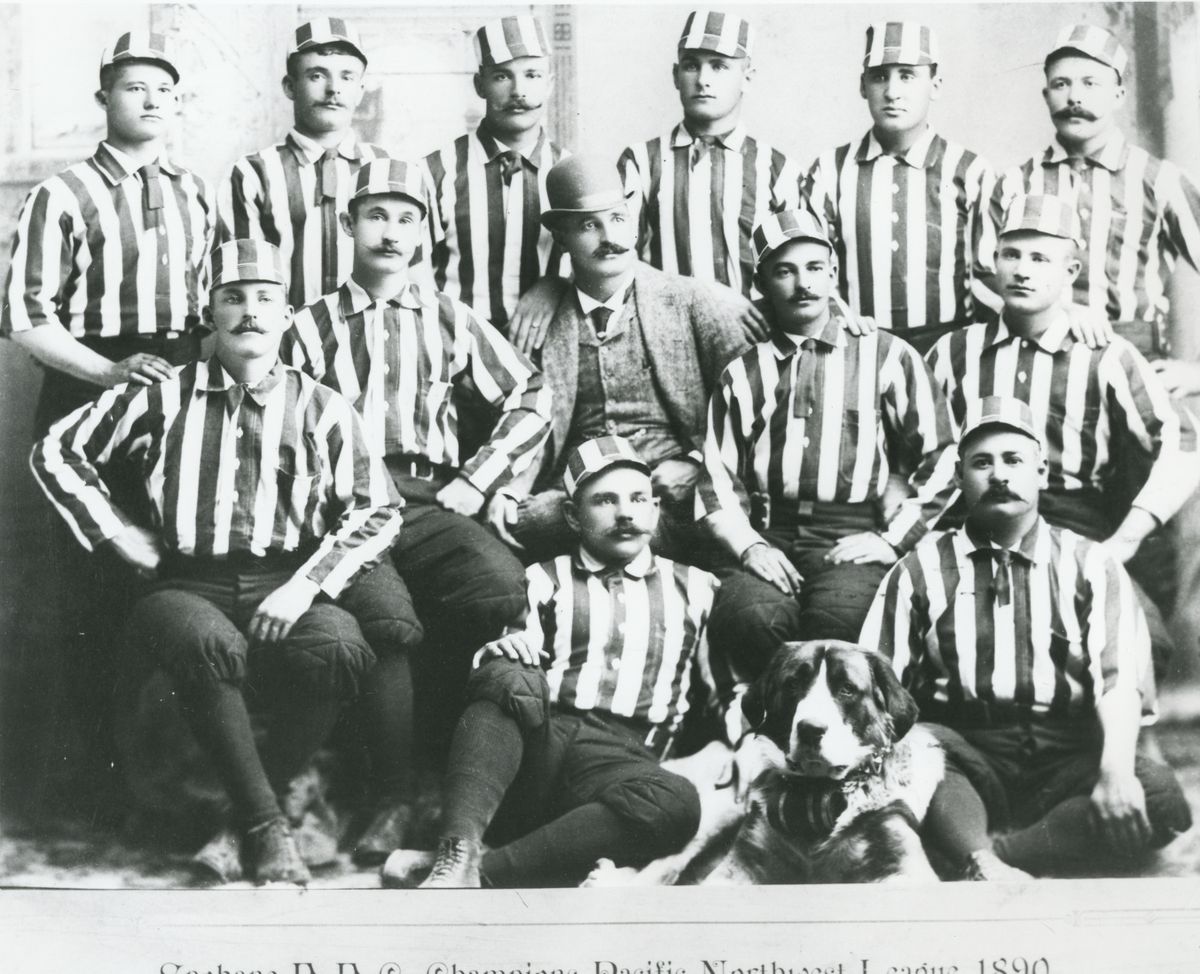

The next Sunday, Barnes broke out distinctive new uniforms that included navy blue pants and stockings with white shirts and caps marked with broad vertical navy stripes. The home season ended two weeks later, on Sept. 21, with a 19-5 victory over Portland.

Spokane wound up the season with a three-week, 13-game road trip. Borchers clinched the pennant Sept. 28-29 with consecutive victories at Seattle. On Oct. 6, a day off, Klopf, who had been relegated to a utility role, married Ida Kean of Tacoma.

The Spokanes coasted to the title with a 61-35 record, 6½ games ahead of Tacoma. Ward, who hit .367, won the batting title. Polhemus, at .340, was second. No home-run figures were published, but Turner, who had hit three in one game at Portland on Aug. 28, clearly led the league. Huston, who had been 13-3 at Galveston, led pitchers with a 28-8 record.

Epilogue

Spokane seemed certain to win again in 1891.

Klopf, Borchers, Turner and Polhemus returned, along with Huston, who reported late after a fling with the California League. Huston’s arrival allowed Klopf to switch to the infield.

On June 24, Spokane had an 18-19 record. But it won 12 of the next 14 games to take over first place and by early August, after a nine-game win streak, its record had improved to 42-25. On Sept. 16, the Spokanes led Portland by 3½ games with 10 to play.

But they lost eight, the Oregonians won eight and settled the race at home by beating Spokane 9-1 on Oct. 3.

That winter, Barnes took over the Portland franchise and, the next year, managed the Western League’s Minneapolis club. On Sept. 15, 1893, at St. Paul, he ran 100 yards in 9 3/5 seconds, allegedly a U.S. record. He opened the 20th century as a promoter of physical fitness in England, Australia and China. Then, he returned to the Northwest in 1909 as part owner and manager at Butte. He repeated that role at Aberdeen in 1915 before living out his life in Seattle.

Ward, Huston, Peeples, McGuirk and Borchers played into the 20th century. The first three died before they were 50. So did Jevne, who after several seasons as an umpire, passed away after falling from a third-floor hotel window in Denver.

Polhemus hit .351 to win the 1891 batting title. Klopf, who pitched the 1891 opener and the second game in 1892, rejoined Spokane as a full-time infielder in 1903 and, at 37, hit .335.

Borchers found more controversy. After the 1891 season, he married Maggie Kelly in Coeur d’Alene. Ten years later, early in his third season with Oakland, he skipped town with Gracie Miller, a prominent businessman’s daughter.

Recalling the scandalous incident, a cousin, Linda Voyles Nelson of Portland, said they were located in Ogden, Utah, and that, within the year, he divorced Maggie and married Gracie. But after his new bride died in late 1902, Borchers returned to Sacramento, bought a dairy, remarried and died in 1938 after losing a leg to diabetes.

The Twickenham baseball grounds stood for two decades and served as the site of a celebrated 1902 engagement for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. A casino had opened down the bluff, at the foot of Boone Avenue, during the 1890 season. By mid-decade, it had been joined by other amusements and soon became Natatorium Park, the area’s favorite recreation facility for three generations. Professional and semipro teams played on its ballfield until World War II.

The modern-era Spokane Indians will open the city’s 99th season of professional baseball on June 18.