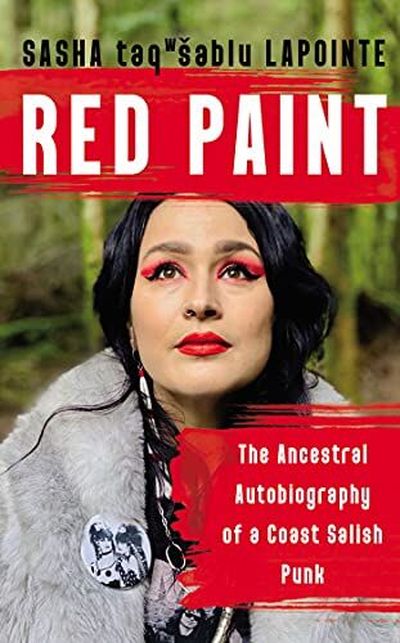

Review: ‘Red Paint’ is a memoir that touches your heart

We may never know exactly the beat of the drums inside the longhouse celebrations that had members of the Coast Salish dancing until dawn.

That, as author Sasha taqwšablu LaPointe points out in her riveting memoir “Red Paint,” is a private ceremony. It would be disrespectful to publicly talk about the rituals the Indigenous people of the Puget Sound had to practice in secret after white settlers outlawed the traditions generations ago.

But it’s easy to listen to the driving drumbeats of Bikini Kill, whose raucous rhythms have been shaking the Pacific Northwest for the past 32 years. Even if you’ve missed them, they’ll start their 2022 world tour next month and arrive back in their hometown of Olympia in September.

That is the soundtrack that sets ancient and contemporary cultures colliding in a book that carries the subtitle “The Ancestral Autobiography of a Coast Salish Punk.” The story lives up to its colorful title.

“Red Paint” is an honest, thoughtful look at the history of the Nooksack and Upper Skagit communities told from the viewpoint of a millennial. This is more than a search to find oneself, however. It is also a retrospective of the suffering inflicted on generations of Native peoples.

LaPointe grew up on the move in a transient family who fought the spirits of violent past, setting them at times in bowling alleys, old churches and trailer parks. She would later surf couches while studying for two master’s degrees and following a partner who toured with a punk band.

Moving was also a part of her heritage, once nomadic by choice, then by the force of white men who landed in ships on the shores and began renaming the countryside in their image.

LaPointe tracks a family tradition back to her great-great grandmother who traveled with her river-wandering husband, a fisherman, a logger and itinerate field hand. Great-great grandmother would carry a roll of linoleum with her wherever they moved and would unroll it like flooring when they found a place to sleep. It was her way of carrying a comfort of home. That symbolism becomes a theme for LaPointe’s own freewheeling lifestyle.

But don’t chalk this up to some millennial restlessness. This has deep roots.

“I realized I wasn’t sure what permanence looked like because we weren’t meant to survive,” LaPointe writes. “My family, my tribe, my ancestors, we were something temporary to the settlers. Something that would eventually go away. Whether by disease or alcohol or poverty, our genocide was inevitable to them. I looked at the smoke pluming from the metal chimneys of the small reservation houses along the highway. But here we were, existing in our impermanent homes.”

“Red Paint” is a search for healing as much as self-awareness tracked through the strength of the Salish women of her family. She descends from tribal royalty in a family tree that evaded smallpox, genocide, chemical dependency and domestic abuse.

LaPointe faces her own monsters. There’s the 40-year-old man who violated her at age 10, the uncle whose house her family shared as a young teen, the boy who date raped her in the woods. LaPointe reminds us of the pain that lingers long after the men who robbed her of her security and self-esteem have gone.

With the encouragement of a college writing instructor, LaPointe channels her trauma onto the page. She finds a poet’s voice and in this work a prose narrative that flows like the pace of a punk rock party amid a backdrop of cultural pop touchstones “Twin Peaks” and “The Goonies,” along with the music of Joy Division, Nick Cave and P.J. Harvey.

The trauma of rape also parallels the pain of her ancestors, watching their homes and land usurped and pillaged by invading foreigners. The details are of the Coast Salish. But it’s a story shared by communities that carry names like Spokane, Seattle, Wichita and Kalamazoo, where the streets are named for people who arrived from faraway places.

“Everything …” LaPointe writes, “was named after the settlers, everything but the place itself.”

LaPointe makes you feel the loss of the culture she wants to reconnect with, to find again and maybe discover her own source of strength and healing.

By the end of “Red Paint,” if you find a hankering to burn some sage, listen to Bikini Kill or download “Poison Garden 1” and “Poison Garden 2” from Seattle post-punk band Medusa Stare, you’re not alone.

“Red Paint” is the kind of story that soaks through your skin and touches your heart.

Ron Sylvester has been a journalist for more than 40 years with publications including the Orange County Register, Las Vegas Sun, Wichita Eagle and USA Today. He currently lives in rural Kansas.